Kerem Oktar

Identifying, Evaluating, and Mitigating Risks of AI Thought Partnerships

May 22, 2025Abstract:Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems have historically been used as tools that execute narrowly defined tasks. Yet recent advances in AI have unlocked possibilities for a new class of models that genuinely collaborate with humans in complex reasoning, from conceptualizing problems to brainstorming solutions. Such AI thought partners enable novel forms of collaboration and extended cognition, yet they also pose major risks-including and beyond risks of typical AI tools and agents. In this commentary, we systematically identify risks of AI thought partners through a novel framework that identifies risks at multiple levels of analysis, including Real-time, Individual, and Societal risks arising from collaborative cognition (RISc). We leverage this framework to propose concrete metrics for risk evaluation, and finally suggest specific mitigation strategies for developers and policymakers. As AI thought partners continue to proliferate, these strategies can help prevent major harms and ensure that humans actively benefit from productive thought partnerships.

Large Language Models Are More Persuasive Than Incentivized Human Persuaders

May 14, 2025

Abstract:We directly compare the persuasion capabilities of a frontier large language model (LLM; Claude Sonnet 3.5) against incentivized human persuaders in an interactive, real-time conversational quiz setting. In this preregistered, large-scale incentivized experiment, participants (quiz takers) completed an online quiz where persuaders (either humans or LLMs) attempted to persuade quiz takers toward correct or incorrect answers. We find that LLM persuaders achieved significantly higher compliance with their directional persuasion attempts than incentivized human persuaders, demonstrating superior persuasive capabilities in both truthful (toward correct answers) and deceptive (toward incorrect answers) contexts. We also find that LLM persuaders significantly increased quiz takers' accuracy, leading to higher earnings, when steering quiz takers toward correct answers, and significantly decreased their accuracy, leading to lower earnings, when steering them toward incorrect answers. Overall, our findings suggest that AI's persuasion capabilities already exceed those of humans that have real-money bonuses tied to performance. Our findings of increasingly capable AI persuaders thus underscore the urgency of emerging alignment and governance frameworks.

Getting aligned on representational alignment

Nov 02, 2023

Abstract:Biological and artificial information processing systems form representations that they can use to categorize, reason, plan, navigate, and make decisions. How can we measure the extent to which the representations formed by these diverse systems agree? Do similarities in representations then translate into similar behavior? How can a system's representations be modified to better match those of another system? These questions pertaining to the study of representational alignment are at the heart of some of the most active research areas in cognitive science, neuroscience, and machine learning. For example, cognitive scientists measure the representational alignment of multiple individuals to identify shared cognitive priors, neuroscientists align fMRI responses from multiple individuals into a shared representational space for group-level analyses, and ML researchers distill knowledge from teacher models into student models by increasing their alignment. Unfortunately, there is limited knowledge transfer between research communities interested in representational alignment, so progress in one field often ends up being rediscovered independently in another. Thus, greater cross-field communication would be advantageous. To improve communication between these fields, we propose a unifying framework that can serve as a common language between researchers studying representational alignment. We survey the literature from all three fields and demonstrate how prior work fits into this framework. Finally, we lay out open problems in representational alignment where progress can benefit all three of these fields. We hope that our work can catalyze cross-disciplinary collaboration and accelerate progress for all communities studying and developing information processing systems. We note that this is a working paper and encourage readers to reach out with their suggestions for future revisions.

Can Humans Do Less-Than-One-Shot Learning?

Feb 09, 2022

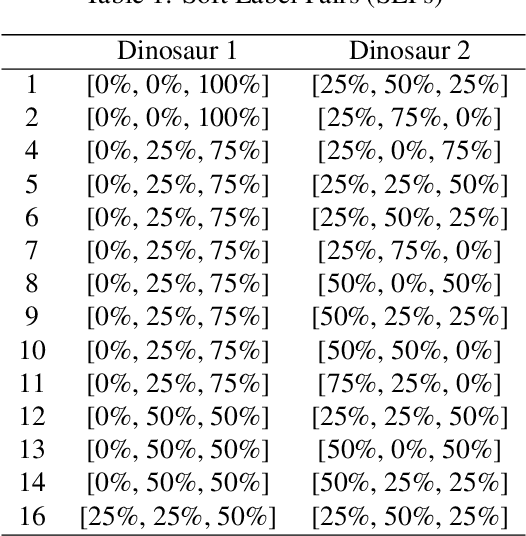

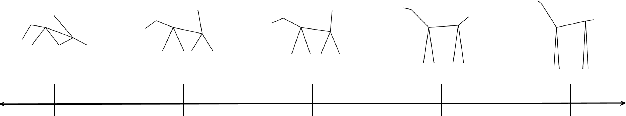

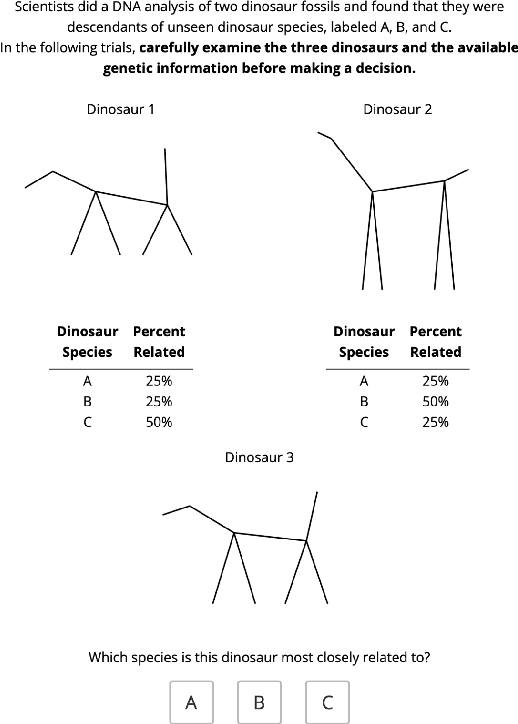

Abstract:Being able to learn from small amounts of data is a key characteristic of human intelligence, but exactly {\em how} small? In this paper, we introduce a novel experimental paradigm that allows us to examine classification in an extremely data-scarce setting, asking whether humans can learn more categories than they have exemplars (i.e., can humans do "less-than-one shot" learning?). An experiment conducted using this paradigm reveals that people are capable of learning in such settings, and provides several insights into underlying mechanisms. First, people can accurately infer and represent high-dimensional feature spaces from very little data. Second, having inferred the relevant spaces, people use a form of prototype-based categorization (as opposed to exemplar-based) to make categorical inferences. Finally, systematic, machine-learnable patterns in responses indicate that people may have efficient inductive biases for dealing with this class of data-scarce problems.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge