Nathaniel D. Daw

Program-Based Strategy Induction for Reinforcement Learning

Feb 26, 2024

Abstract:Typical models of learning assume incremental estimation of continuously-varying decision variables like expected rewards. However, this class of models fails to capture more idiosyncratic, discrete heuristics and strategies that people and animals appear to exhibit. Despite recent advances in strategy discovery using tools like recurrent networks that generalize the classic models, the resulting strategies are often onerous to interpret, making connections to cognition difficult to establish. We use Bayesian program induction to discover strategies implemented by programs, letting the simplicity of strategies trade off against their effectiveness. Focusing on bandit tasks, we find strategies that are difficult or unexpected with classical incremental learning, like asymmetric learning from rewarded and unrewarded trials, adaptive horizon-dependent random exploration, and discrete state switching.

Exploring the hierarchical structure of human plans via program generation

Nov 30, 2023Abstract:Human behavior is inherently hierarchical, resulting from the decomposition of a task into subtasks or an abstract action into concrete actions. However, behavior is typically measured as a sequence of actions, which makes it difficult to infer its hierarchical structure. In this paper, we explore how people form hierarchically-structured plans, using an experimental paradigm that makes hierarchical representations observable: participants create programs that produce sequences of actions in a language with explicit hierarchical structure. This task lets us test two well-established principles of human behavior: utility maximization (i.e. using fewer actions) and minimum description length (MDL; i.e. having a shorter program). We find that humans are sensitive to both metrics, but that both accounts fail to predict a qualitative feature of human-created programs, namely that people prefer programs with reuse over and above the predictions of MDL. We formalize this preference for reuse by extending the MDL account into a generative model over programs, modeling hierarchy choice as the induction of a grammar over actions. Our account can explain the preference for reuse and provides the best prediction of human behavior, going beyond simple accounts of compressibility to highlight a principle that guides hierarchical planning.

Humans decompose tasks by trading off utility and computational cost

Nov 07, 2022

Abstract:Human behavior emerges from planning over elaborate decompositions of tasks into goals, subgoals, and low-level actions. How are these decompositions created and used? Here, we propose and evaluate a normative framework for task decomposition based on the simple idea that people decompose tasks to reduce the overall cost of planning while maintaining task performance. Analyzing 11,117 distinct graph-structured planning tasks, we find that our framework justifies several existing heuristics for task decomposition and makes predictions that can be distinguished from two alternative normative accounts. We report a behavioral study of task decomposition ($N=806$) that uses 30 randomly sampled graphs, a larger and more diverse set than that of any previous behavioral study on this topic. We find that human responses are more consistent with our framework for task decomposition than alternative normative accounts and are most consistent with a heuristic -- betweenness centrality -- that is justified by our approach. Taken together, our results provide new theoretical insight into the computational principles underlying the intelligent structuring of goal-directed behavior.

Using Natural Language and Program Abstractions to Instill Human Inductive Biases in Machines

May 23, 2022

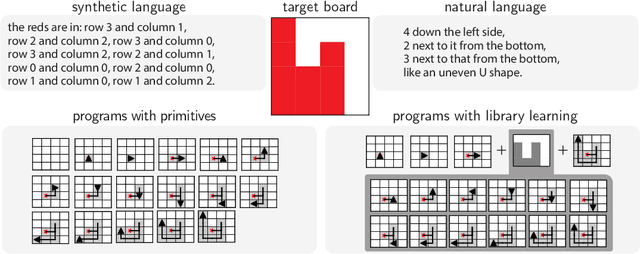

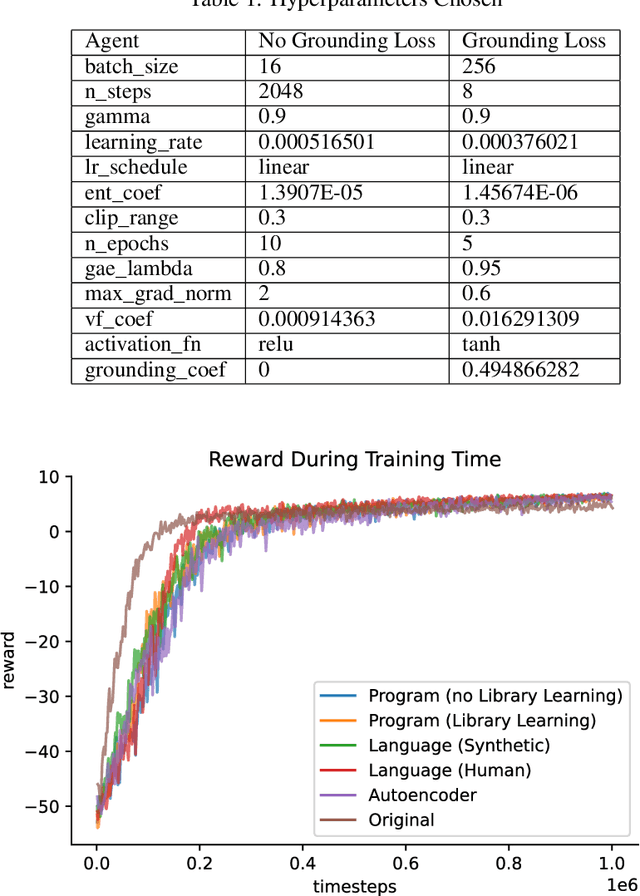

Abstract:Strong inductive biases are a key component of human intelligence, allowing people to quickly learn a variety of tasks. Although meta-learning has emerged as an approach for endowing neural networks with useful inductive biases, agents trained by meta-learning may acquire very different strategies from humans. We show that co-training these agents on predicting representations from natural language task descriptions and from programs induced to generate such tasks guides them toward human-like inductive biases. Human-generated language descriptions and program induction with library learning both result in more human-like behavior in downstream meta-reinforcement learning agents than less abstract controls (synthetic language descriptions, program induction without library learning), suggesting that the abstraction supported by these representations is key.

Disentangling Abstraction from Statistical Pattern Matching in Human and Machine Learning

Apr 04, 2022

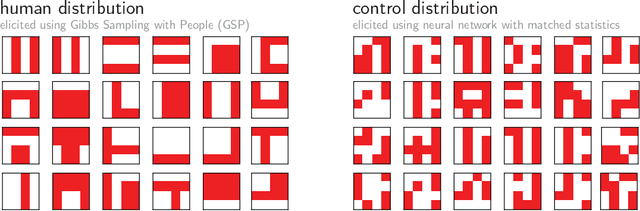

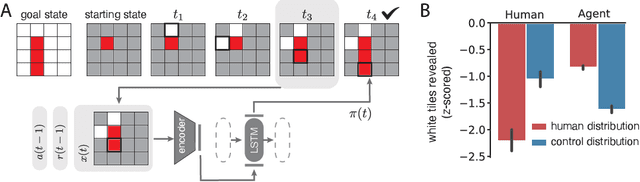

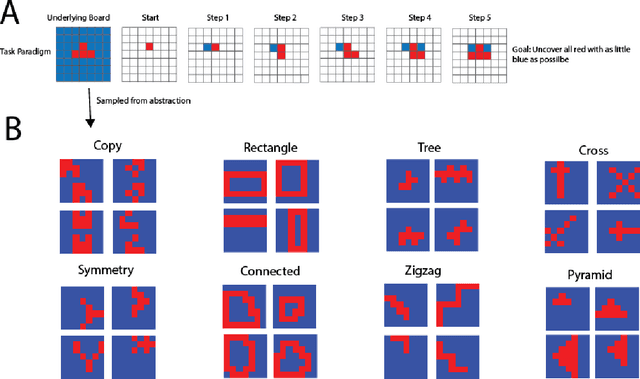

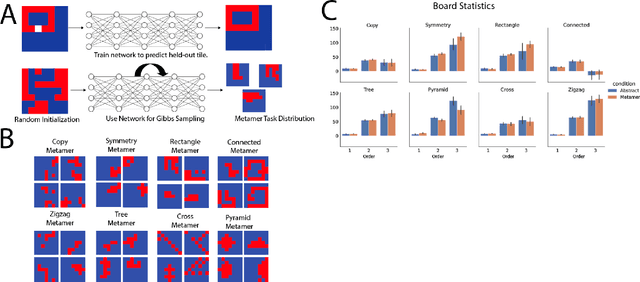

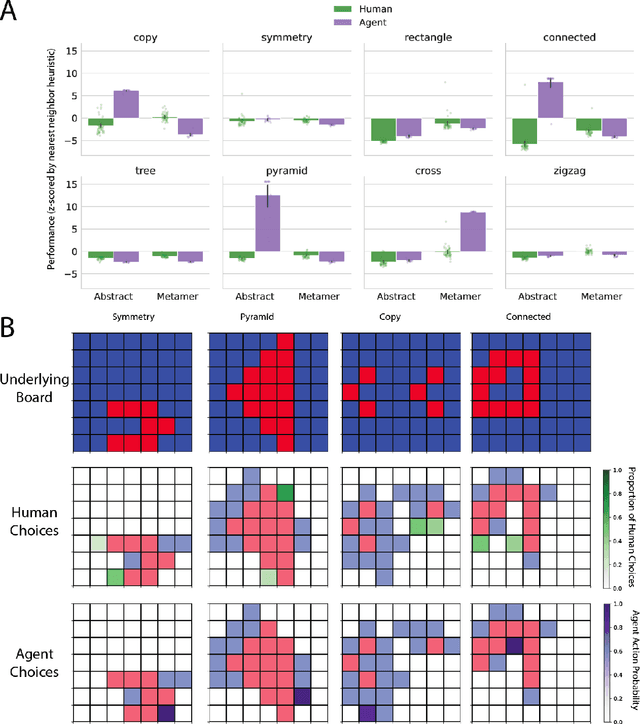

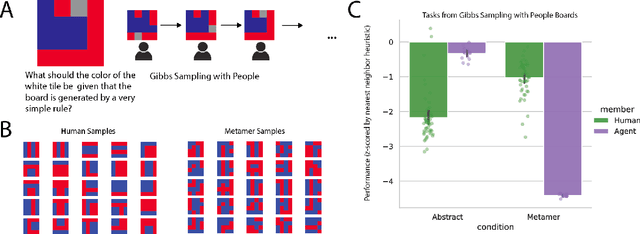

Abstract:The ability to acquire abstract knowledge is a hallmark of human intelligence and is believed by many to be one of the core differences between humans and neural network models. Agents can be endowed with an inductive bias towards abstraction through meta-learning, where they are trained on a distribution of tasks that share some abstract structure that can be learned and applied. However, because neural networks are hard to interpret, it can be difficult to tell whether agents have learned the underlying abstraction, or alternatively statistical patterns that are characteristic of that abstraction. In this work, we compare the performance of humans and agents in a meta-reinforcement learning paradigm in which tasks are generated from abstract rules. We define a novel methodology for building "task metamers" that closely match the statistics of the abstract tasks but use a different underlying generative process, and evaluate performance on both abstract and metamer tasks. In our first set of experiments, we found that humans perform better at abstract tasks than metamer tasks whereas a widely-used meta-reinforcement learning agent performs worse on the abstract tasks than the matched metamers. In a second set of experiments, we base the tasks on abstractions derived directly from empirically identified human priors. We utilize the same procedure to generate corresponding metamer tasks, and see the same double dissociation between humans and agents. This work provides a foundation for characterizing differences between humans and machine learning that can be used in future work towards developing machines with human-like behavior.

Meta-Learning of Compositional Task Distributions in Humans and Machines

Oct 05, 2020

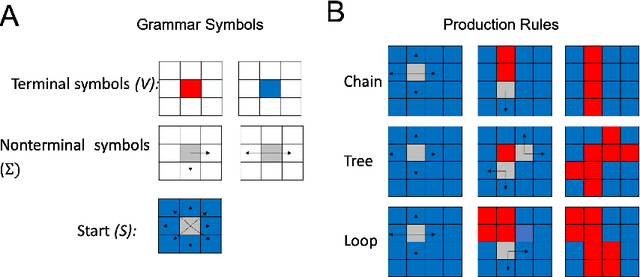

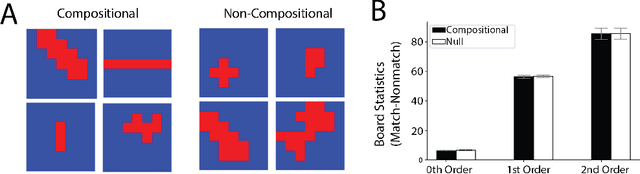

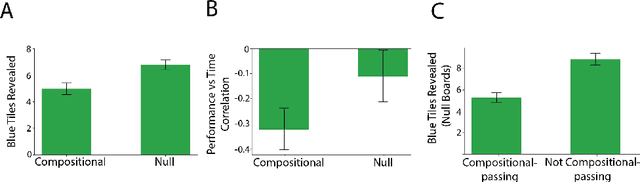

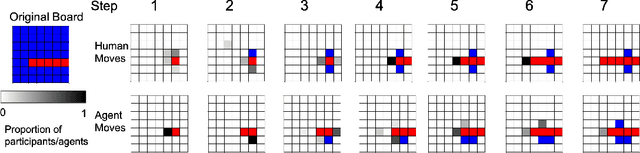

Abstract:Modern machine learning systems struggle with sample efficiency and are usually trained with enormous amounts of data for each task. This is in sharp contrast with humans, who often learn with very little data. In recent years, meta-learning, in which one trains on a family of tasks (i.e. a task distribution), has emerged as an approach to improving the sample complexity of machine learning systems and to closing the gap between human and machine learning. However, in this paper, we argue that current meta-learning approaches still differ significantly from human learning. We argue that humans learn over tasks by constructing compositional generative models and using these to generalize, whereas current meta-learning methods are biased toward the use of simpler statistical patterns. To highlight this difference, we construct a new meta-reinforcement learning task with a compositional task distribution. We also introduce a novel approach to constructing a "null task distribution" with the same statistical complexity as the compositional distribution but without explicit compositionality. We train a standard meta-learning agent, a recurrent network trained with model-free reinforcement learning, and compare it with human performance across the two task distributions. We find that humans do better in the compositional task distribution whereas the agent does better in the non-compositional null task distribution -- despite comparable statistical complexity. This work highlights a particular difference between human learning and current meta-learning models, introduces a task that displays this difference, and paves the way for future work on human-like meta-learning.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge