Gregory Valiant

Tony

OpenAI GPT-5 System Card

Dec 19, 2025Abstract:This is the system card published alongside the OpenAI GPT-5 launch, August 2025. GPT-5 is a unified system with a smart and fast model that answers most questions, a deeper reasoning model for harder problems, and a real-time router that quickly decides which model to use based on conversation type, complexity, tool needs, and explicit intent (for example, if you say 'think hard about this' in the prompt). The router is continuously trained on real signals, including when users switch models, preference rates for responses, and measured correctness, improving over time. Once usage limits are reached, a mini version of each model handles remaining queries. This system card focuses primarily on gpt-5-thinking and gpt-5-main, while evaluations for other models are available in the appendix. The GPT-5 system not only outperforms previous models on benchmarks and answers questions more quickly, but -- more importantly -- is more useful for real-world queries. We've made significant advances in reducing hallucinations, improving instruction following, and minimizing sycophancy, and have leveled up GPT-5's performance in three of ChatGPT's most common uses: writing, coding, and health. All of the GPT-5 models additionally feature safe-completions, our latest approach to safety training to prevent disallowed content. Similarly to ChatGPT agent, we have decided to treat gpt-5-thinking as High capability in the Biological and Chemical domain under our Preparedness Framework, activating the associated safeguards. While we do not have definitive evidence that this model could meaningfully help a novice to create severe biological harm -- our defined threshold for High capability -- we have chosen to take a precautionary approach.

On the Entropy Calibration of Language Models

Nov 15, 2025

Abstract:We study the problem of entropy calibration, which asks whether a language model's entropy over generations matches its log loss on human text. Past work found that models are miscalibrated, with entropy per step increasing (and text quality decreasing) as generations grow longer. This error accumulation is a fundamental problem in autoregressive models, and the standard solution is to truncate the distribution, which improves text quality at the cost of diversity. In this paper, we ask: is miscalibration likely to improve with scale, and is it theoretically possible to calibrate without tradeoffs? To build intuition, we first study a simplified theoretical setting to characterize the scaling behavior of miscalibration with respect to dataset size. We find that the scaling behavior depends on the power law exponent of the data distribution -- in particular, for a power law exponent close to 1, the scaling exponent is close to 0, meaning that miscalibration improves very slowly with scale. Next, we measure miscalibration empirically in language models ranging from 0.5B to 70B parameters. We find that the observed scaling behavior is similar to what is predicted by the simplified setting: our fitted scaling exponents for text are close to 0, meaning that larger models accumulate error at a similar rate as smaller ones. This scaling (or, lack thereof) provides one explanation for why we sample from larger models with similar amounts of truncation as smaller models, even though the larger models are of higher quality. However, truncation is not a satisfying solution because it comes at the cost of increased log loss. In theory, is it even possible to reduce entropy while preserving log loss? We prove that it is possible, if we assume access to a black box which can fit models to predict the future entropy of text.

Attainability of Two-Point Testing Rates for Finite-Sample Location Estimation

Feb 09, 2025Abstract:LeCam's two-point testing method yields perhaps the simplest lower bound for estimating the mean of a distribution: roughly, if it is impossible to well-distinguish a distribution centered at $\mu$ from the same distribution centered at $\mu+\Delta$, then it is impossible to estimate the mean by better than $\Delta/2$. It is setting-dependent whether or not a nearly matching upper bound is attainable. We study the conditions under which the two-point testing lower bound can be attained for univariate mean estimation; both in the setting of location estimation (where the distribution is known up to translation) and adaptive location estimation (unknown distribution). Roughly, we will say an estimate nearly attains the two-point testing lower bound if it incurs error that is at most polylogarithmically larger than the Hellinger modulus of continuity for $\tilde{\Omega}(n)$ samples. Adaptive location estimation is particularly interesting as some distributions admit much better guarantees than sub-Gaussian rates (e.g. $\operatorname{Unif}(\mu-1,\mu+1)$ permits error $\Theta(\frac{1}{n})$, while the sub-Gaussian rate is $\Theta(\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}})$), yet it is not obvious whether these rates may be adaptively attained by one unified approach. Our main result designs an algorithm that nearly attains the two-point testing rate for mixtures of symmetric, log-concave distributions with a common mean. Moreover, this algorithm runs in near-linear time and is parameter-free. In contrast, we show the two-point testing rate is not nearly attainable even for symmetric, unimodal distributions. We complement this with results for location estimation, showing the two-point testing rate is nearly attainable for unimodal distributions, but unattainable for symmetric distributions.

Discovering Data Structures: Nearest Neighbor Search and Beyond

Nov 05, 2024

Abstract:We propose a general framework for end-to-end learning of data structures. Our framework adapts to the underlying data distribution and provides fine-grained control over query and space complexity. Crucially, the data structure is learned from scratch, and does not require careful initialization or seeding with candidate data structures/algorithms. We first apply this framework to the problem of nearest neighbor search. In several settings, we are able to reverse-engineer the learned data structures and query algorithms. For 1D nearest neighbor search, the model discovers optimal distribution (in)dependent algorithms such as binary search and variants of interpolation search. In higher dimensions, the model learns solutions that resemble k-d trees in some regimes, while in others, they have elements of locality-sensitive hashing. The model can also learn useful representations of high-dimensional data and exploit them to design effective data structures. We also adapt our framework to the problem of estimating frequencies over a data stream, and believe it could also be a powerful discovery tool for new problems.

Adaptive and oblivious statistical adversaries are equivalent

Oct 17, 2024

Abstract:We resolve a fundamental question about the ability to perform a statistical task, such as learning, when an adversary corrupts the sample. Such adversaries are specified by the types of corruption they can make and their level of knowledge about the sample. The latter distinguishes between sample-adaptive adversaries which know the contents of the sample when choosing the corruption, and sample-oblivious adversaries, which do not. We prove that for all types of corruptions, sample-adaptive and sample-oblivious adversaries are \emph{equivalent} up to polynomial factors in the sample size. This resolves the main open question introduced by \cite{BLMT22} and further explored in \cite{CHLLN23}. Specifically, consider any algorithm $A$ that solves a statistical task even when a sample-oblivious adversary corrupts its input. We show that there is an algorithm $A'$ that solves the same task when the corresponding sample-adaptive adversary corrupts its input. The construction of $A'$ is simple and maintains the computational efficiency of $A$: It requests a polynomially larger sample than $A$ uses and then runs $A$ on a uniformly random subsample. One of our main technical tools is a new structural result relating two distributions defined on sunflowers which may be of independent interest.

Near-Optimal Mean Estimation with Unknown, Heteroskedastic Variances

Dec 05, 2023

Abstract:Given data drawn from a collection of Gaussian variables with a common mean but different and unknown variances, what is the best algorithm for estimating their common mean? We present an intuitive and efficient algorithm for this task. As different closed-form guarantees can be hard to compare, the Subset-of-Signals model serves as a benchmark for heteroskedastic mean estimation: given $n$ Gaussian variables with an unknown subset of $m$ variables having variance bounded by 1, what is the optimal estimation error as a function of $n$ and $m$? Our algorithm resolves this open question up to logarithmic factors, improving upon the previous best known estimation error by polynomial factors when $m = n^c$ for all $0<c<1$. Of particular note, we obtain error $o(1)$ with $m = \tilde{O}(n^{1/4})$ variance-bounded samples, whereas previous work required $m = \tilde{\Omega}(n^{1/2})$. Finally, we show that in the multi-dimensional setting, even for $d=2$, our techniques enable rates comparable to knowing the variance of each sample.

Testing with Non-identically Distributed Samples

Nov 19, 2023

Abstract:We examine the extent to which sublinear-sample property testing and estimation applies to settings where samples are independently but not identically distributed. Specifically, we consider the following distributional property testing framework: Suppose there is a set of distributions over a discrete support of size $k$, $\textbf{p}_1, \textbf{p}_2,\ldots,\textbf{p}_T$, and we obtain $c$ independent draws from each distribution. Suppose the goal is to learn or test a property of the average distribution, $\textbf{p}_{\mathrm{avg}}$. This setup models a number of important practical settings where the individual distributions correspond to heterogeneous entities -- either individuals, chronologically distinct time periods, spatially separated data sources, etc. From a learning standpoint, even with $c=1$ samples from each distribution, $\Theta(k/\varepsilon^2)$ samples are necessary and sufficient to learn $\textbf{p}_{\mathrm{avg}}$ to within error $\varepsilon$ in TV distance. To test uniformity or identity -- distinguishing the case that $\textbf{p}_{\mathrm{avg}}$ is equal to some reference distribution, versus has $\ell_1$ distance at least $\varepsilon$ from the reference distribution, we show that a linear number of samples in $k$ is necessary given $c=1$ samples from each distribution. In contrast, for $c \ge 2$, we recover the usual sublinear sample testing of the i.i.d. setting: we show that $O(\sqrt{k}/\varepsilon^2 + 1/\varepsilon^4)$ samples are sufficient, matching the optimal sample complexity in the i.i.d. case in the regime where $\varepsilon \ge k^{-1/4}$. Additionally, we show that in the $c=2$ case, there is a constant $\rho > 0$ such that even in the linear regime with $\rho k$ samples, no tester that considers the multiset of samples (ignoring which samples were drawn from the same $\textbf{p}_i$) can perform uniformity testing.

One-sided Matrix Completion from Two Observations Per Row

Jun 06, 2023

Abstract:Given only a few observed entries from a low-rank matrix $X$, matrix completion is the problem of imputing the missing entries, and it formalizes a wide range of real-world settings that involve estimating missing data. However, when there are too few observed entries to complete the matrix, what other aspects of the underlying matrix can be reliably recovered? We study one such problem setting, that of "one-sided" matrix completion, where our goal is to recover the right singular vectors of $X$, even in the regime where recovering the left singular vectors is impossible, which arises when there are more rows than columns and very few observations. We propose a natural algorithm that involves imputing the missing values of the matrix $X^TX$ and show that even with only two observations per row in $X$, we can provably recover $X^TX$ as long as we have at least $\Omega(r^2 d \log d)$ rows, where $r$ is the rank and $d$ is the number of columns. We evaluate our algorithm on one-sided recovery of synthetic data and low-coverage genome sequencing. In these settings, our algorithm substantially outperforms standard matrix completion and a variety of direct factorization methods.

Lexinvariant Language Models

May 24, 2023

Abstract:Token embeddings, a mapping from discrete lexical symbols to continuous vectors, are at the heart of any language model (LM). However, lexical symbol meanings can also be determined and even redefined by their structural role in a long context. In this paper, we ask: is it possible for a language model to be performant without \emph{any} fixed token embeddings? Such a language model would have to rely entirely on the co-occurence and repetition of tokens in the context rather than the \textit{a priori} identity of any token. To answer this, we study \textit{lexinvariant}language models that are invariant to lexical symbols and therefore do not need fixed token embeddings in practice. First, we prove that we can construct a lexinvariant LM to converge to the true language model at a uniform rate that is polynomial in terms of the context length, with a constant factor that is sublinear in the vocabulary size. Second, to build a lexinvariant LM, we simply encode tokens using random Gaussian vectors, such that each token maps to the same representation within each sequence but different representations across sequences. Empirically, we demonstrate that it can indeed attain perplexity comparable to that of a standard language model, given a sufficiently long context. We further explore two properties of the lexinvariant language models: First, given text generated from a substitution cipher of English, it implicitly implements Bayesian in-context deciphering and infers the mapping to the underlying real tokens with high accuracy. Second, it has on average 4X better accuracy over synthetic in-context reasoning tasks. Finally, we discuss regularizing standard language models towards lexinvariance and potential practical applications.

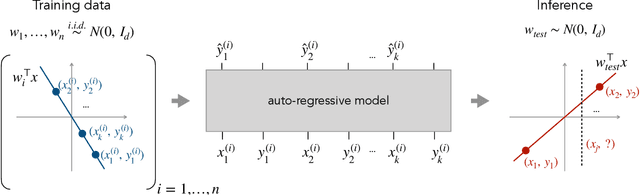

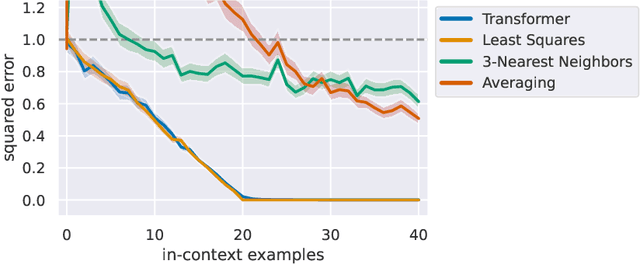

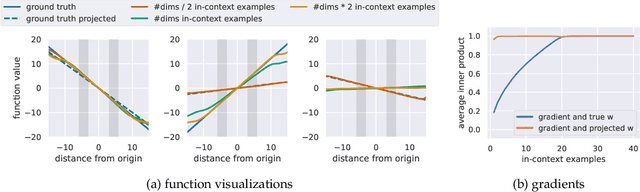

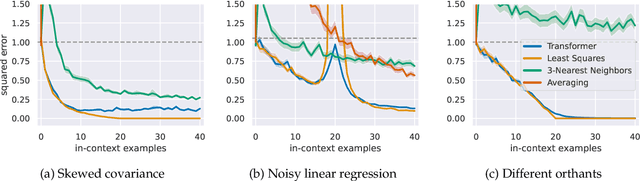

What Can Transformers Learn In-Context? A Case Study of Simple Function Classes

Aug 01, 2022

Abstract:In-context learning refers to the ability of a model to condition on a prompt sequence consisting of in-context examples (input-output pairs corresponding to some task) along with a new query input, and generate the corresponding output. Crucially, in-context learning happens only at inference time without any parameter updates to the model. While large language models such as GPT-3 exhibit some ability to perform in-context learning, it is unclear what the relationship is between tasks on which this succeeds and what is present in the training data. To make progress towards understanding in-context learning, we consider the well-defined problem of training a model to in-context learn a function class (e.g., linear functions): that is, given data derived from some functions in the class, can we train a model to in-context learn "most" functions from this class? We show empirically that standard Transformers can be trained from scratch to perform in-context learning of linear functions -- that is, the trained model is able to learn unseen linear functions from in-context examples with performance comparable to the optimal least squares estimator. In fact, in-context learning is possible even under two forms of distribution shift: (i) between the training data of the model and inference-time prompts, and (ii) between the in-context examples and the query input during inference. We also show that we can train Transformers to in-context learn more complex function classes -- namely sparse linear functions, two-layer neural networks, and decision trees -- with performance that matches or exceeds task-specific learning algorithms. Our code and models are available at https://github.com/dtsip/in-context-learning .

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge