Marilyn Albert

Teresa

Prospective Learning: Back to the Future

Jan 19, 2022

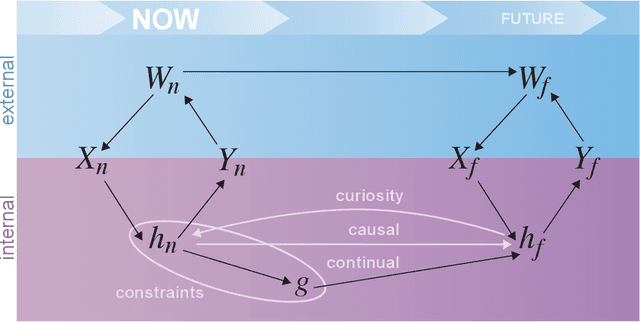

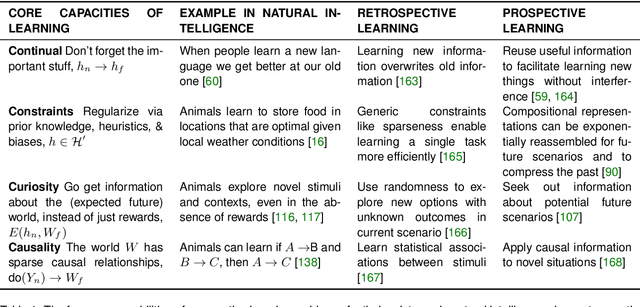

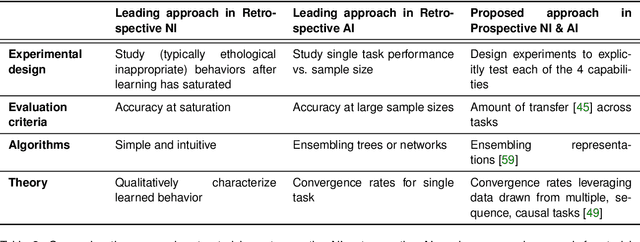

Abstract:Research on both natural intelligence (NI) and artificial intelligence (AI) generally assumes that the future resembles the past: intelligent agents or systems (what we call 'intelligence') observe and act on the world, then use this experience to act on future experiences of the same kind. We call this 'retrospective learning'. For example, an intelligence may see a set of pictures of objects, along with their names, and learn to name them. A retrospective learning intelligence would merely be able to name more pictures of the same objects. We argue that this is not what true intelligence is about. In many real world problems, both NIs and AIs will have to learn for an uncertain future. Both must update their internal models to be useful for future tasks, such as naming fundamentally new objects and using these objects effectively in a new context or to achieve previously unencountered goals. This ability to learn for the future we call 'prospective learning'. We articulate four relevant factors that jointly define prospective learning. Continual learning enables intelligences to remember those aspects of the past which it believes will be most useful in the future. Prospective constraints (including biases and priors) facilitate the intelligence finding general solutions that will be applicable to future problems. Curiosity motivates taking actions that inform future decision making, including in previously unmet situations. Causal estimation enables learning the structure of relations that guide choosing actions for specific outcomes, even when the specific action-outcome contingencies have never been observed before. We argue that a paradigm shift from retrospective to prospective learning will enable the communities that study intelligence to unite and overcome existing bottlenecks to more effectively explain, augment, and engineer intelligences.

Multidimensional representations in late-life depression: convergence in neuroimaging, cognition, clinical symptomatology and genetics

Oct 25, 2021

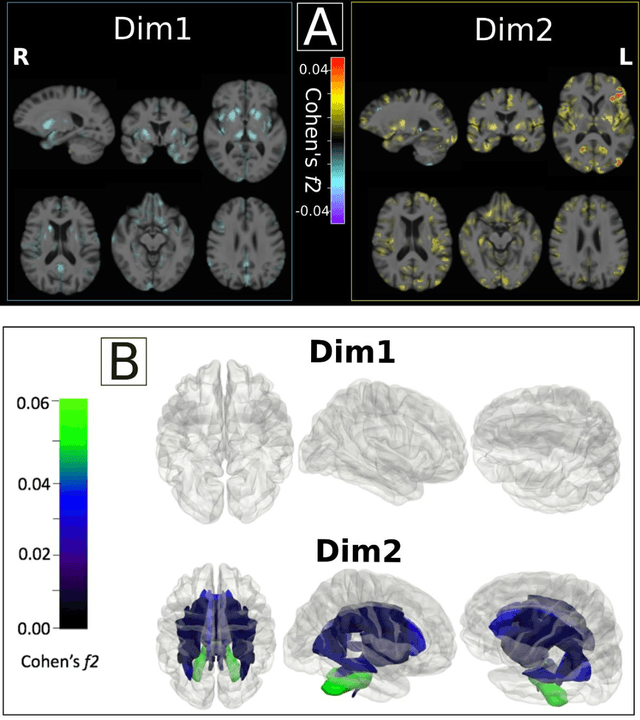

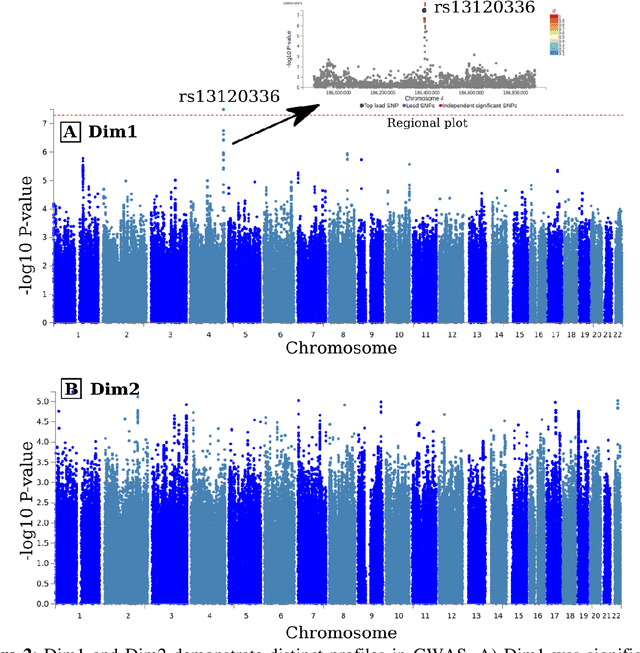

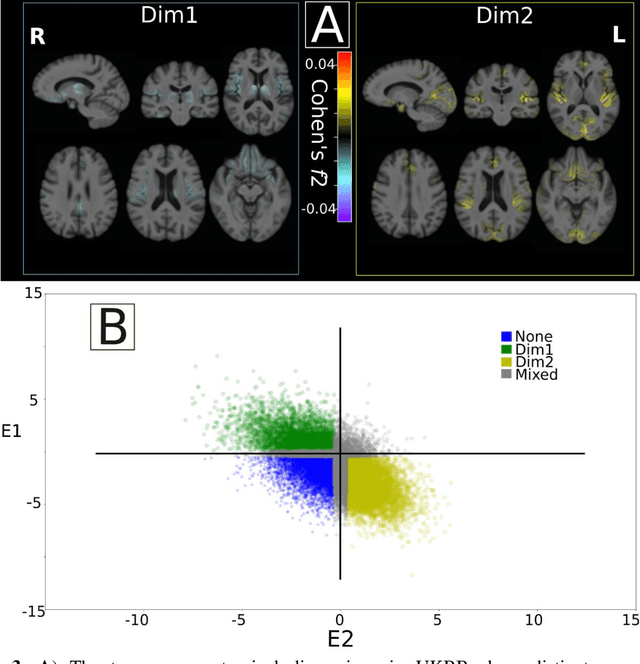

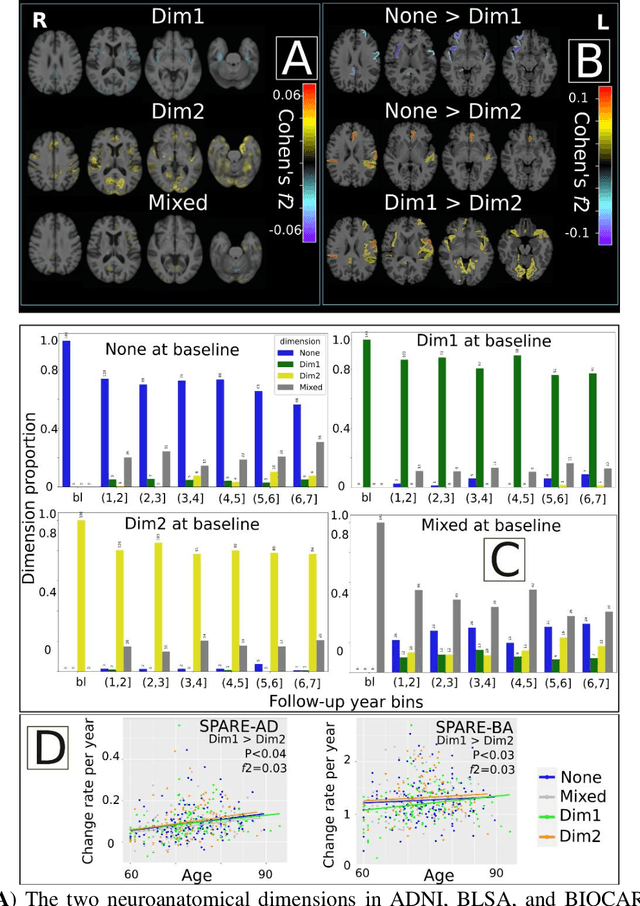

Abstract:Late-life depression (LLD) is characterized by considerable heterogeneity in clinical manifestation. Unraveling such heterogeneity would aid in elucidating etiological mechanisms and pave the road to precision and individualized medicine. We sought to delineate, cross-sectionally and longitudinally, disease-related heterogeneity in LLD linked to neuroanatomy, cognitive functioning, clinical symptomatology, and genetic profiles. Multimodal data from a multicentre sample (N=996) were analyzed. A semi-supervised clustering method (HYDRA) was applied to regional grey matter (GM) brain volumes to derive dimensional representations. Two dimensions were identified, which accounted for the LLD-related heterogeneity in voxel-wise GM maps, white matter (WM) fractional anisotropy (FA), neurocognitive functioning, clinical phenotype, and genetics. Dimension one (Dim1) demonstrated relatively preserved brain anatomy without WM disruptions relative to healthy controls. In contrast, dimension two (Dim2) showed widespread brain atrophy and WM integrity disruptions, along with cognitive impairment and higher depression severity. Moreover, one de novo independent genetic variant (rs13120336) was significantly associated with Dim 1 but not with Dim 2. Notably, the two dimensions demonstrated significant SNP-based heritability of 18-27% within the general population (N=12,518 in UKBB). Lastly, in a subset of individuals having longitudinal measurements, Dim2 demonstrated a more rapid longitudinal decrease in GM and brain age, and was more likely to progress to Alzheimers disease, compared to Dim1 (N=1,413 participants and 7,225 scans from ADNI, BLSA, and BIOCARD datasets).

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge