Hilke Schellmann

Addressing Pitfalls in Auditing Practices of Automatic Speech Recognition Technologies: A Case Study of People with Aphasia

Jun 10, 2025

Abstract:Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) has transformed daily tasks from video transcription to workplace hiring. ASR systems' growing use warrants robust and standardized auditing approaches to ensure automated transcriptions of high and equitable quality. This is especially critical for people with speech and language disorders (such as aphasia) who may disproportionately depend on ASR systems to navigate everyday life. In this work, we identify three pitfalls in existing standard ASR auditing procedures, and demonstrate how addressing them impacts audit results via a case study of six popular ASR systems' performance for aphasia speakers. First, audits often adhere to a single method of text standardization during data pre-processing, which (a) masks variability in ASR performance from applying different standardization methods, and (b) may not be consistent with how users - especially those from marginalized speech communities - would want their transcriptions to be standardized. Second, audits often display high-level demographic findings without further considering performance disparities among (a) more nuanced demographic subgroups, and (b) relevant covariates capturing acoustic information from the input audio. Third, audits often rely on a single gold-standard metric -- the Word Error Rate -- which does not fully capture the extent of errors arising from generative AI models, such as transcription hallucinations. We propose a more holistic auditing framework that accounts for these three pitfalls, and exemplify its results in our case study, finding consistently worse ASR performance for aphasia speakers relative to a control group. We call on practitioners to implement these robust ASR auditing practices that remain flexible to the rapidly changing ASR landscape.

Careless Whisper: Speech-to-Text Hallucination Harms

Feb 12, 2024

Abstract:Speech-to-text services aim to transcribe input audio as accurately as possible. They increasingly play a role in everyday life, for example in personal voice assistants or in customer-company interactions. We evaluate Open AI's Whisper, a state-of-the-art service outperforming industry competitors. While many of Whisper's transcriptions were highly accurate, we found that roughly 1% of audio transcriptions contained entire hallucinated phrases or sentences, which did not exist in any form in the underlying audio. We thematically analyze the Whisper-hallucinated content, finding that 38% of hallucinations include explicit harms such as violence, made up personal information, or false video-based authority. We further provide hypotheses on why hallucinations occur, uncovering potential disparities due to speech type by health status. We call on industry practitioners to ameliorate these language-model-based hallucinations in Whisper, and to raise awareness of potential biases in downstream applications of speech-to-text models.

External Stability Auditing to Test the Validity of Personality Prediction in AI Hiring

Jan 23, 2022

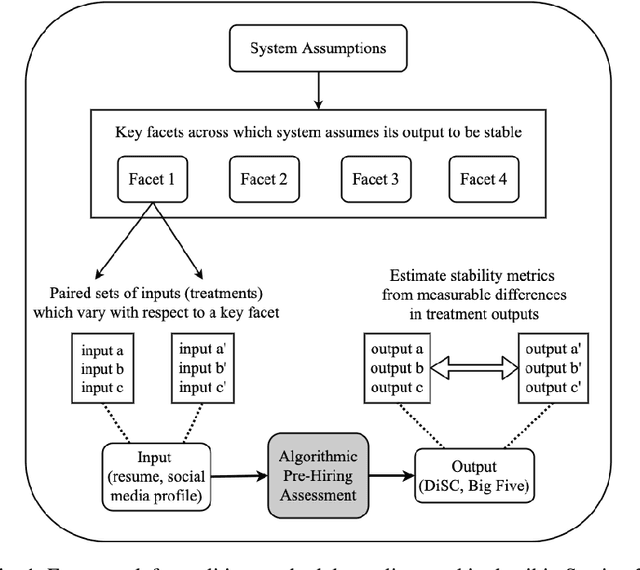

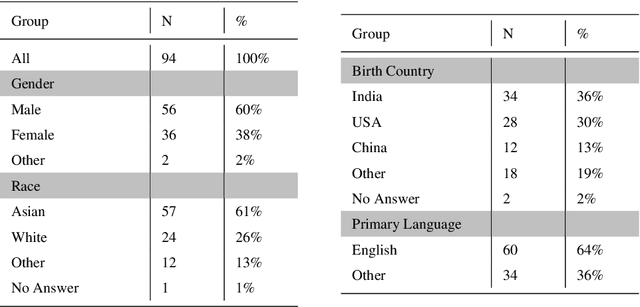

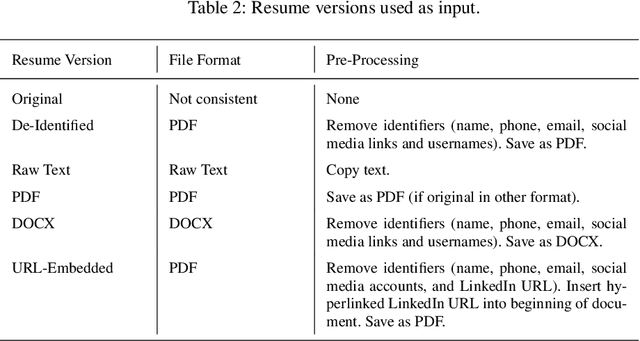

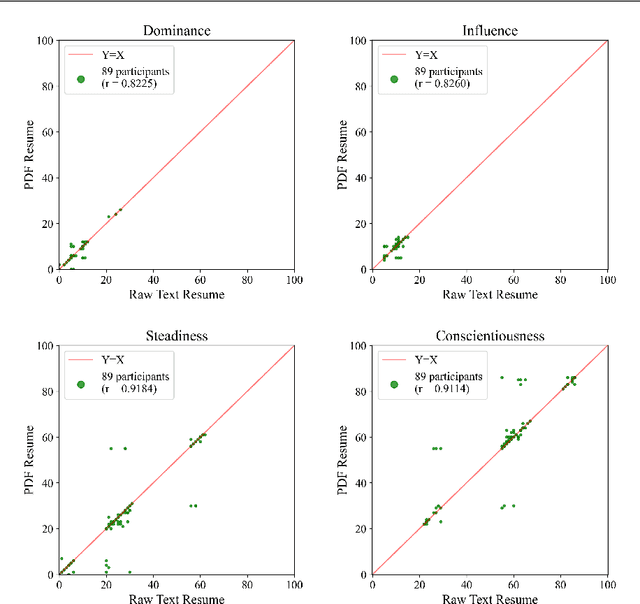

Abstract:Automated hiring systems are among the fastest-developing of all high-stakes AI systems. Among these are algorithmic personality tests that use insights from psychometric testing, and promise to surface personality traits indicative of future success based on job seekers' resumes or social media profiles. We interrogate the validity of such systems using stability of the outputs they produce, noting that reliability is a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition for validity. Our approach is to (a) develop a methodology for an external audit of stability of predictions made by algorithmic personality tests, and (b) instantiate this methodology in an audit of two systems, Humantic AI and Crystal. Crucially, rather than challenging or affirming the assumptions made in psychometric testing -- that personality is a meaningful and measurable construct, and that personality traits are indicative of future success on the job -- we frame our methodology around testing the underlying assumptions made by the vendors of the algorithmic personality tests themselves. In our audit of Humantic AI and Crystal, we find that both systems show substantial instability with respect to key facets of measurement, and so cannot be considered valid testing instruments. For example, Crystal frequently computes different personality scores if the same resume is given in PDF vs. in raw text format, violating the assumption that the output of an algorithmic personality test is stable across job-irrelevant variations in the input. Among other notable findings is evidence of persistent -- and often incorrect -- data linkage by Humantic AI.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge