Elizabeth Hillman

Prospective Learning: Back to the Future

Jan 19, 2022

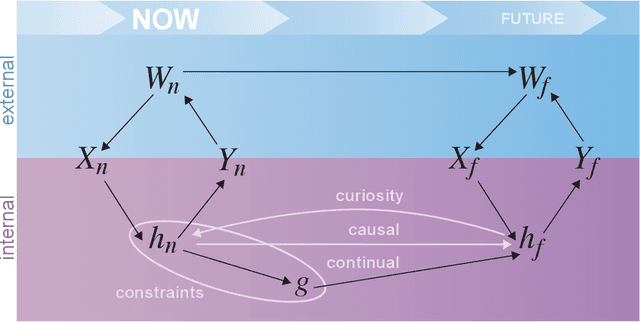

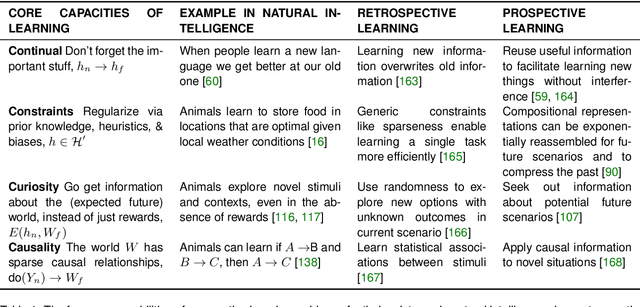

Abstract:Research on both natural intelligence (NI) and artificial intelligence (AI) generally assumes that the future resembles the past: intelligent agents or systems (what we call 'intelligence') observe and act on the world, then use this experience to act on future experiences of the same kind. We call this 'retrospective learning'. For example, an intelligence may see a set of pictures of objects, along with their names, and learn to name them. A retrospective learning intelligence would merely be able to name more pictures of the same objects. We argue that this is not what true intelligence is about. In many real world problems, both NIs and AIs will have to learn for an uncertain future. Both must update their internal models to be useful for future tasks, such as naming fundamentally new objects and using these objects effectively in a new context or to achieve previously unencountered goals. This ability to learn for the future we call 'prospective learning'. We articulate four relevant factors that jointly define prospective learning. Continual learning enables intelligences to remember those aspects of the past which it believes will be most useful in the future. Prospective constraints (including biases and priors) facilitate the intelligence finding general solutions that will be applicable to future problems. Curiosity motivates taking actions that inform future decision making, including in previously unmet situations. Causal estimation enables learning the structure of relations that guide choosing actions for specific outcomes, even when the specific action-outcome contingencies have never been observed before. We argue that a paradigm shift from retrospective to prospective learning will enable the communities that study intelligence to unite and overcome existing bottlenecks to more effectively explain, augment, and engineer intelligences.

Penalized matrix decomposition for denoising, compression, and improved demixing of functional imaging data

Jul 17, 2018

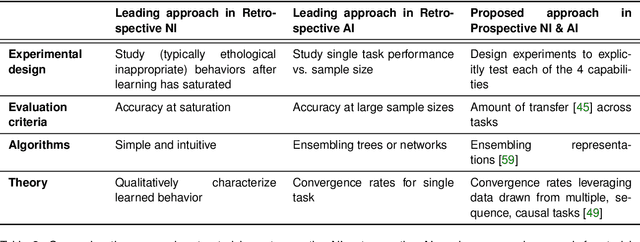

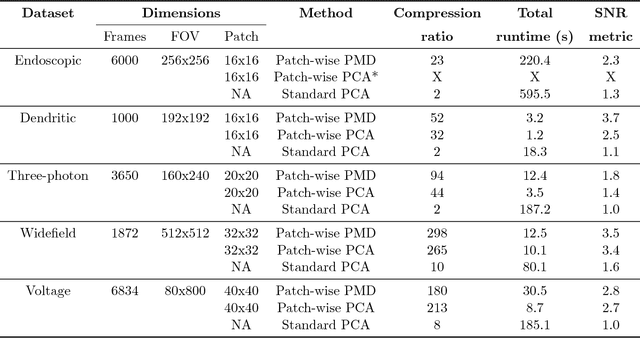

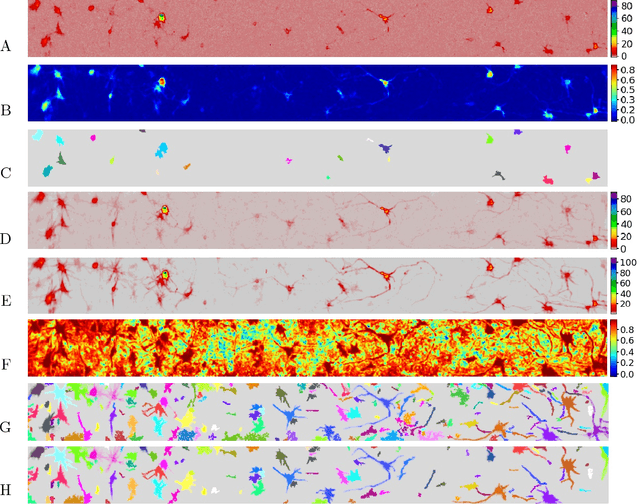

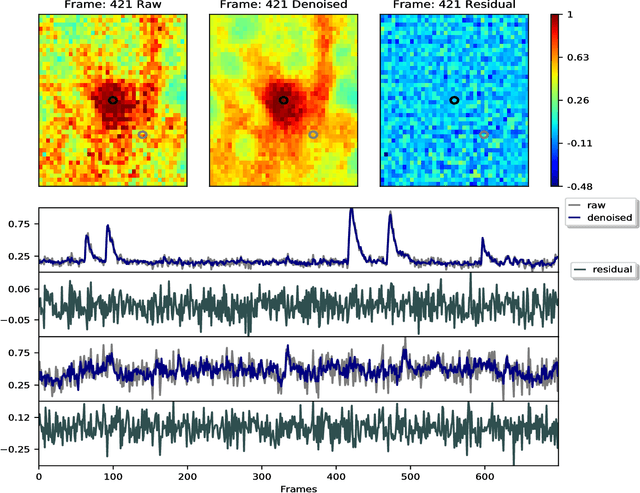

Abstract:Calcium imaging has revolutionized systems neuroscience, providing the ability to image large neural populations with single-cell resolution. The resulting datasets are quite large, which has presented a barrier to routine open sharing of this data, slowing progress in reproducible research. State of the art methods for analyzing this data are based on non-negative matrix factorization (NMF); these approaches solve a non-convex optimization problem, and are effective when good initializations are available, but can break down in low-SNR settings where common initialization approaches fail. Here we introduce an approach to compressing and denoising functional imaging data. The method is based on a spatially-localized penalized matrix decomposition (PMD) of the data to separate (low-dimensional) signal from (temporally-uncorrelated) noise. This approach can be applied in parallel on local spatial patches and is therefore highly scalable, does not impose non-negativity constraints or require stringent identifiability assumptions (leading to significantly more robust results compared to NMF), and estimates all parameters directly from the data, so no hand-tuning is required. We have applied the method to a wide range of functional imaging data (including one-photon, two-photon, three-photon, widefield, somatic, axonal, dendritic, calcium, and voltage imaging datasets): in all cases, we observe ~2-4x increases in SNR and compression rates of 20-300x with minimal visible loss of signal, with no adjustment of hyperparameters; this in turn facilitates the process of demixing the observed activity into contributions from individual neurons. We focus on two challenging applications: dendritic calcium imaging data and voltage imaging data in the context of optogenetic stimulation. In both cases, we show that our new approach leads to faster and much more robust extraction of activity from the data.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge