Umashanthi Pavalanathan

Mind Your POV: Convergence of Articles and Editors Towards Wikipedia's Neutrality Norm

Sep 18, 2018

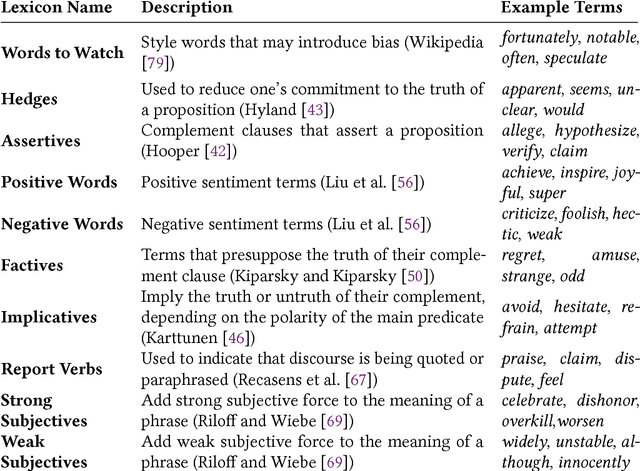

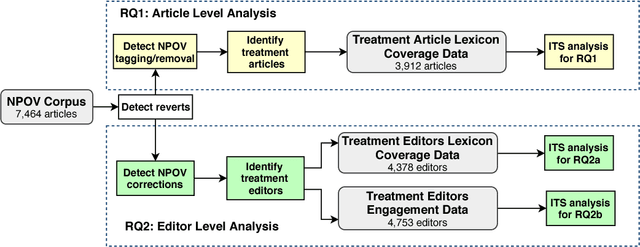

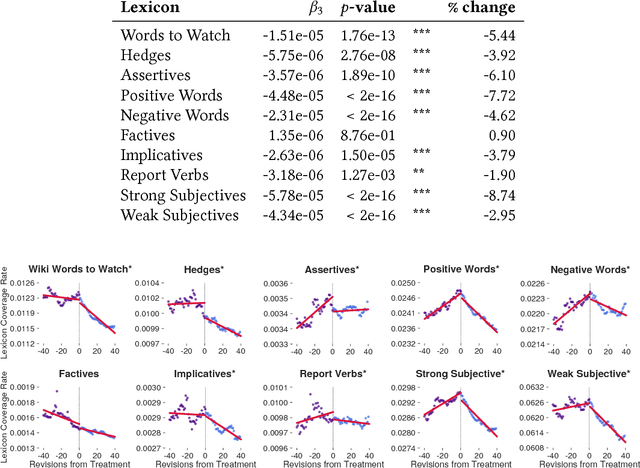

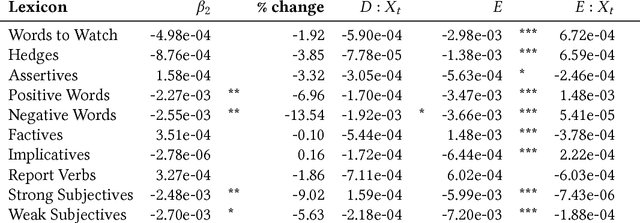

Abstract:Wikipedia has a strong norm of writing in a 'neutral point of view' (NPOV). Articles that violate this norm are tagged, and editors are encouraged to make corrections. But the impact of this tagging system has not been quantitatively measured. Does NPOV tagging help articles to converge to the desired style? Do NPOV corrections encourage editors to adopt this style? We study these questions using a corpus of NPOV-tagged articles and a set of lexicons associated with biased language. An interrupted time series analysis shows that after an article is tagged for NPOV, there is a significant decrease in biased language in the article, as measured by several lexicons. However, for individual editors, NPOV corrections and talk page discussions yield no significant change in the usage of words in most of these lexicons, including Wikipedia's own list of 'words to watch.' This suggests that NPOV tagging and discussion does improve content, but has less success enculturating editors to the site's linguistic norms.

* ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing (CSCW), 2018

Emoticons vs. Emojis on Twitter: A Causal Inference Approach

Oct 28, 2015

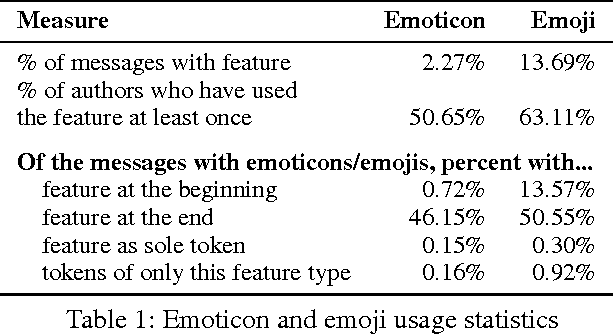

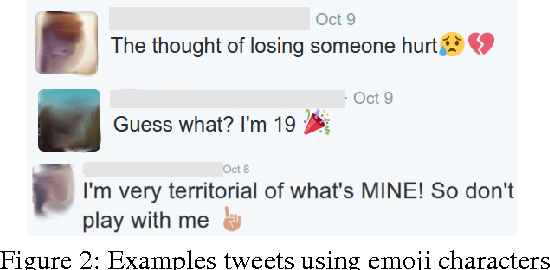

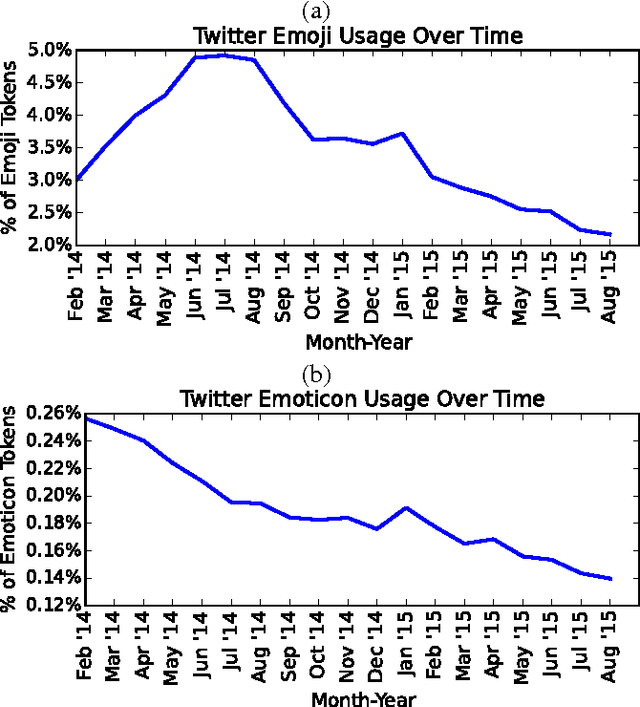

Abstract:Online writing lacks the non-verbal cues present in face-to-face communication, which provide additional contextual information about the utterance, such as the speaker's intention or affective state. To fill this void, a number of orthographic features, such as emoticons, expressive lengthening, and non-standard punctuation, have become popular in social media services including Twitter and Instagram. Recently, emojis have been introduced to social media, and are increasingly popular. This raises the question of whether these predefined pictographic characters will come to replace earlier orthographic methods of paralinguistic communication. In this abstract, we attempt to shed light on this question, using a matching approach from causal inference to test whether the adoption of emojis causes individual users to employ fewer emoticons in their text on Twitter.

Confounds and Consequences in Geotagged Twitter Data

Aug 22, 2015

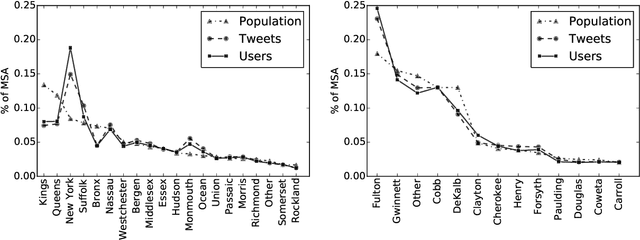

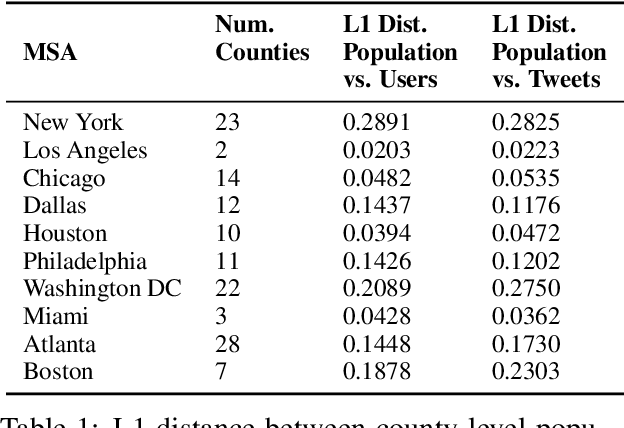

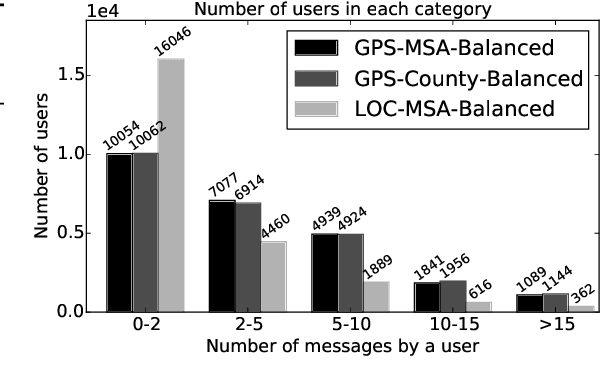

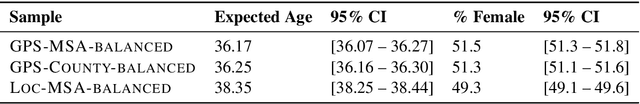

Abstract:Twitter is often used in quantitative studies that identify geographically-preferred topics, writing styles, and entities. These studies rely on either GPS coordinates attached to individual messages, or on the user-supplied location field in each profile. In this paper, we compare these data acquisition techniques and quantify the biases that they introduce; we also measure their effects on linguistic analysis and text-based geolocation. GPS-tagging and self-reported locations yield measurably different corpora, and these linguistic differences are partially attributable to differences in dataset composition by age and gender. Using a latent variable model to induce age and gender, we show how these demographic variables interact with geography to affect language use. We also show that the accuracy of text-based geolocation varies with population demographics, giving the best results for men above the age of 40.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge