Ben Green

editor

Technology Ethics in Action: Critical and Interdisciplinary Perspectives

Feb 03, 2022

Abstract:This special issue interrogates the meaning and impacts of "tech ethics": the embedding of ethics into digital technology research, development, use, and governance. In response to concerns about the social harms associated with digital technologies, many individuals and institutions have articulated the need for a greater emphasis on ethics in digital technology. Yet as more groups embrace the concept of ethics, critical discourses have emerged questioning whose ethics are being centered, whether "ethics" is the appropriate frame for improving technology, and what it means to develop "ethical" technology in practice. This interdisciplinary issue takes up these questions, interrogating the relationships among ethics, technology, and society in action. This special issue engages with the normative and contested notions of ethics itself, how ethics has been integrated with technology across domains, and potential paths forward to support more just and egalitarian technology. Rather than starting from philosophical theories, the authors in this issue orient their articles around the real-world discourses and impacts of tech ethics--i.e., tech ethics in action.

Escaping the "Impossibility of Fairness": From Formal to Substantive Algorithmic Fairness

Aug 12, 2021Abstract:In the face of compounding crises of social and economic inequality, many have turned to algorithmic decision-making to achieve greater fairness in society. As these efforts intensify, reasoning within the burgeoning field of "algorithmic fairness" increasingly shapes how fairness manifests in practice. This paper interrogates whether algorithmic fairness provides the appropriate conceptual and practical tools for enhancing social equality. I argue that the dominant, "formal" approach to algorithmic fairness is ill-equipped as a framework for pursuing equality, as its narrow frame of analysis generates restrictive approaches to reform. In light of these shortcomings, I propose an alternative: a "substantive" approach to algorithmic fairness that centers opposition to social hierarchies and provides a more expansive analysis of how to address inequality. This substantive approach enables more fruitful theorizing about the role of algorithms in combatting oppression. The distinction between formal and substantive algorithmic fairness is exemplified by each approach's responses to the "impossibility of fairness" (an incompatibility between mathematical definitions of algorithmic fairness). While the formal approach requires us to accept the "impossibility of fairness" as a harsh limit on efforts to enhance equality, the substantive approach allows us to escape the "impossibility of fairness" by suggesting reforms that are not subject to this false dilemma and that are better equipped to ameliorate conditions of social oppression.

The Contestation of Tech Ethics: A Sociotechnical Approach to Ethics and Technology in Action

Jun 03, 2021Abstract:Recent controversies related to topics such as fake news, privacy, and algorithmic bias have prompted increased public scrutiny of digital technologies and soul-searching among many of the people associated with their development. In response, the tech industry, academia, civil society, and governments have rapidly increased their attention to "ethics" in the design and use of digital technologies ("tech ethics"). Yet almost as quickly as ethics discourse has proliferated across the world of digital technologies, the limitations of these approaches have also become apparent: tech ethics is vague and toothless, is subsumed into corporate logics and incentives, and has a myopic focus on individual engineers and technology design rather than on the structures and cultures of technology production. As a result of these limitations, many have grown skeptical of tech ethics and its proponents, charging them with "ethics-washing": promoting ethics research and discourse to defuse criticism and government regulation without committing to ethical behavior. By looking at how ethics has been taken up in both science and business in superficial and depoliticizing ways, I recast tech ethics as a terrain of contestation where the central fault line is not whether it is desirable to be ethical, but what "ethics" entails and who gets to define it. This framing highlights the significant limits of current approaches to tech ethics and the importance of studying the formulation and real-world effects of tech ethics. In order to identify and develop more rigorous strategies for reforming digital technologies and the social relations that they mediate, I describe a sociotechnical approach to tech ethics, one that reflexively applies many of tech ethics' own lessons regarding digital technologies to tech ethics itself.

Algorithmic risk assessments can alter human decision-making processes in high-stakes government contexts

Dec 09, 2020

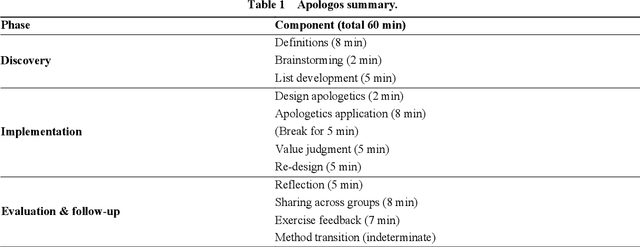

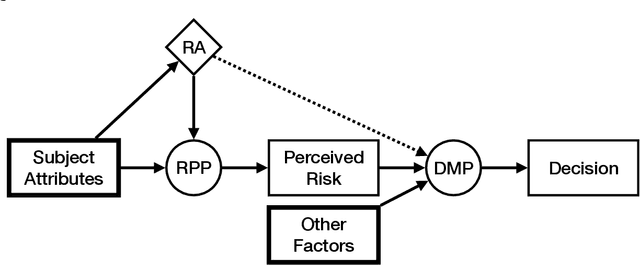

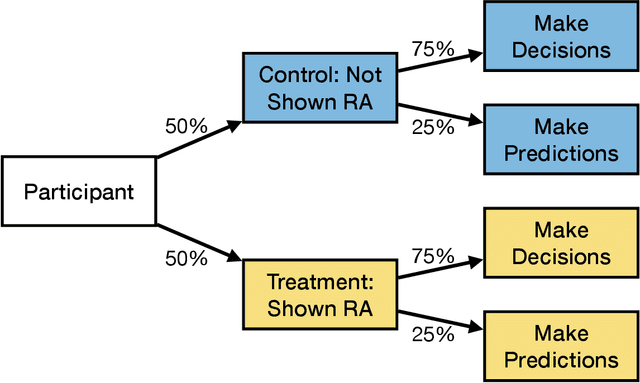

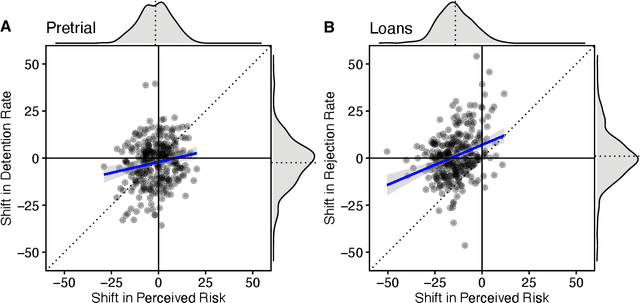

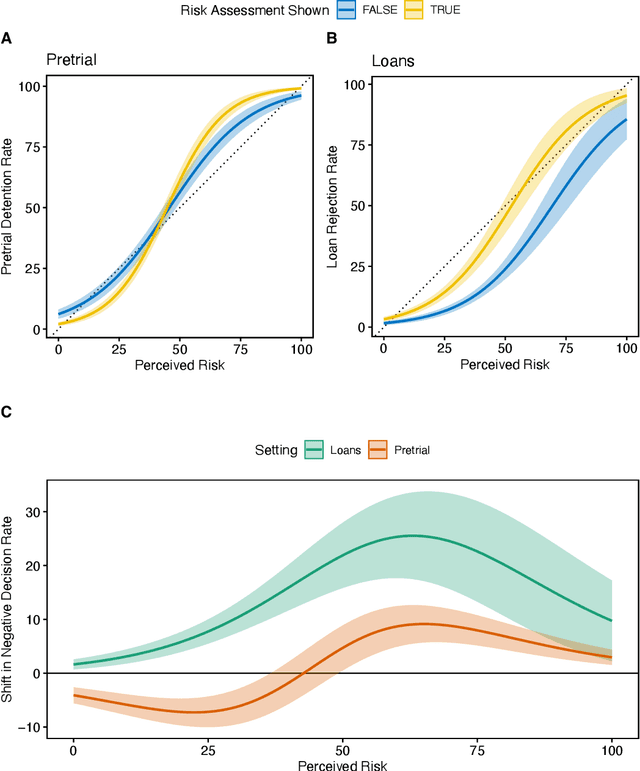

Abstract:Governments are increasingly turning to algorithmic risk assessments when making important decisions, believing that these algorithms will improve public servants' ability to make policy-relevant predictions and thereby lead to more informed decisions. Yet because many policy decisions require balancing risk-minimization with competing social goals, evaluating the impacts of risk assessments requires considering how public servants are influenced by risk assessments when making policy decisions rather than just how accurately these algorithms make predictions. Through an online experiment with 2,140 lay participants simulating two high-stakes government contexts, we provide the first large-scale evidence that risk assessments can systematically alter decision-making processes by increasing the salience of risk as a factor in decisions and that these shifts could exacerbate racial disparities. These results demonstrate that improving human prediction accuracy with algorithms does not necessarily improve human decisions and highlight the need to experimentally test how government algorithms are used by human decision-makers.

Data Science as Political Action: Grounding Data Science in a Politics of Justice

Nov 06, 2018Abstract:In response to recent controversies, the field of data science has rushed to adopt codes of ethics. Such professional codes, however, are ill-equipped to address broad matters of social justice. Instead of ethics codes, I argue, the field must embrace politics. Data scientists must recognize themselves as political actors engaged in normative constructions of society and, as befits political work, evaluate their work according to its downstream material impacts on people's lives. I justify this notion in two parts: first, by articulating why data scientists must recognize themselves as political actors, and second, by describing how the field can evolve toward a deliberative and rigorous grounding in a politics of social justice. Part 1 responds to three common arguments that have been invoked by data scientists when they are challenged to take political positions regarding their work. In confronting these arguments, I will demonstrate why attempting to remain apolitical is itself a political stance--a fundamentally conservative one--and why the field's current attempts to promote "social good" dangerously rely on vague and unarticulated political assumptions. Part 2 proposes a framework for what a politically-engaged data science could look like and how to achieve it, recognizing the challenge of reforming the field in this manner. I conceptualize the process of incorporating politics into data science in four stages: becoming interested in directly addressing social issues, recognizing the politics underlying these issues, redirecting existing methods toward new applications, and, finally, developing new practices and methods that orient data science around a mission of social justice. The path ahead does not require data scientists to abandon their technical expertise, but it does entail expanding their notions of what problems to work on and how to engage with society.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge