Maurizio Serva

Stability of meanings versus rate of replacement of words: an experimental test

Oct 23, 2018

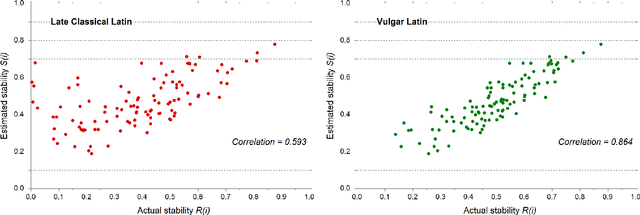

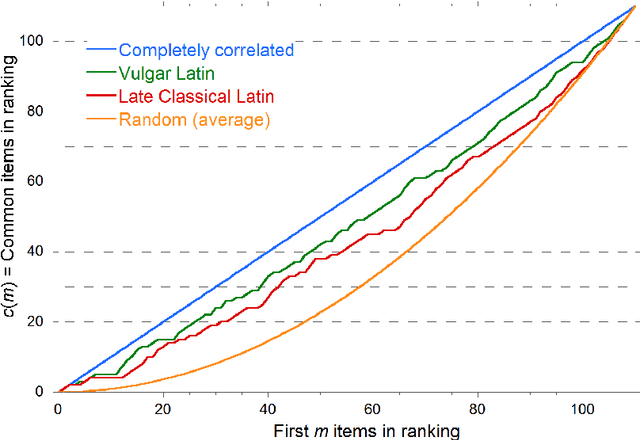

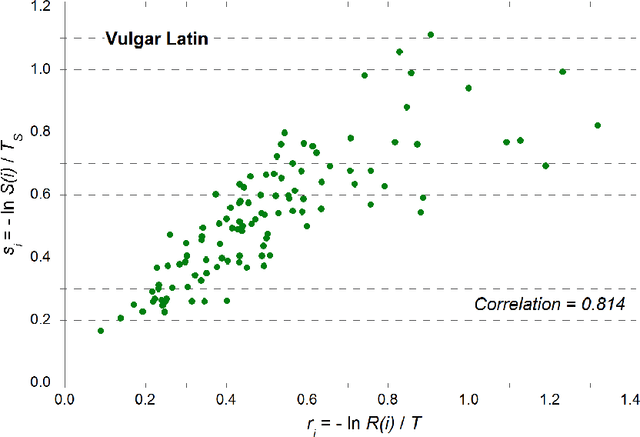

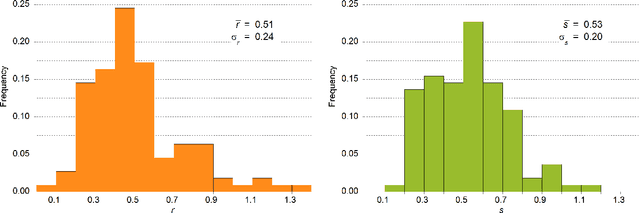

Abstract:The words of a language are randomly replaced in time by new ones, but it has long been known that words corresponding to some items (meanings) are less frequently replaced than others. Usually, the rate of replacement for a given item is not directly observable, but it is inferred by the estimated stability which, on the contrary, is observable. This idea goes back a long way in the lexicostatistical literature, nevertheless nothing ensures that it gives the correct answer. The family of Romance languages allows for a direct test of the estimated stabilities against the replacement rates since the proto-language (Latin) is known and the replacement rates can be explicitly computed. The output of the test is threefold:first, we prove that the standard approach which tries to infer the replacement rates trough the estimated stabilities is sound; second, we are able to rewrite the fundamental formula of Glottochronology for a non universal replacement rate (a rate which depends on the item); third, we give indisputable evidence that the stability ranking is far from being the same for different families of languages. This last result is also supported by comparison with the Malagasy family of dialects. As a side result we also provide some evidence that Vulgar Latin and not Late Classical Latin is at the root of modern Romance languages.

Automated languages phylogeny from Levenshtein distance

Jul 02, 2012

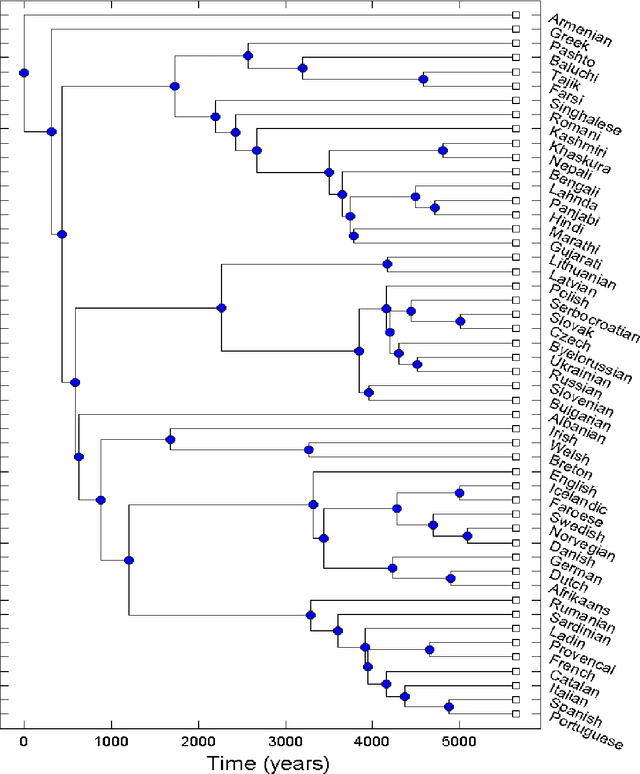

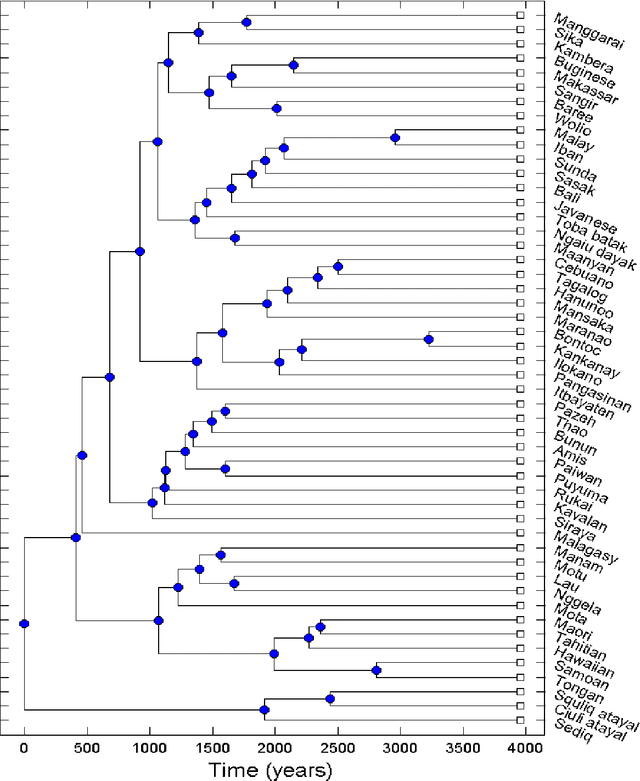

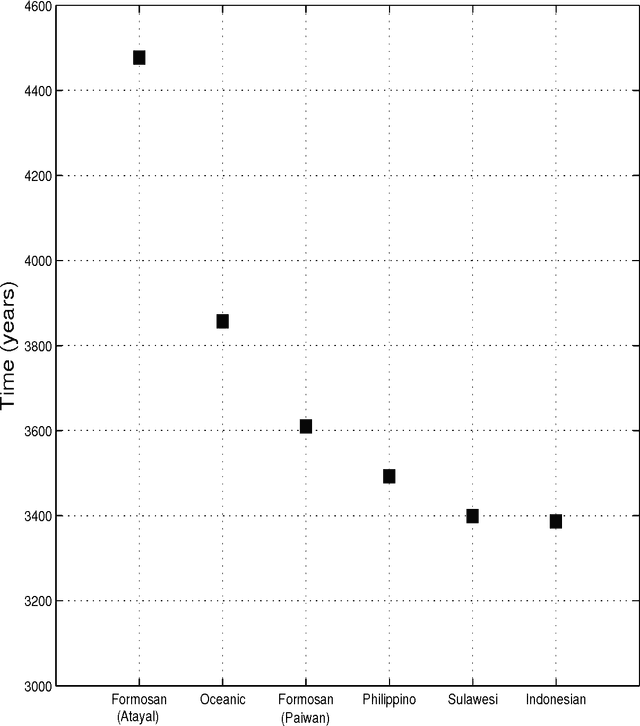

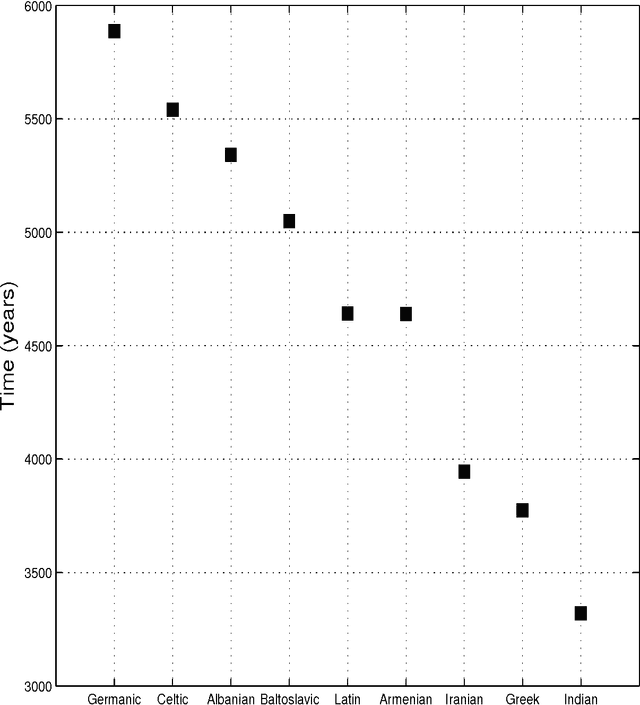

Abstract:Languages evolve over time in a process in which reproduction, mutation and extinction are all possible, similar to what happens to living organisms. Using this similarity it is possible, in principle, to build family trees which show the degree of relatedness between languages. The method used by modern glottochronology, developed by Swadesh in the 1950s, measures distances from the percentage of words with a common historical origin. The weak point of this method is that subjective judgment plays a relevant role. Recently we proposed an automated method that avoids the subjectivity, whose results can be replicated by studies that use the same database and that doesn't require a specific linguistic knowledge. Moreover, the method allows a quick comparison of a large number of languages. We applied our method to the Indo-European and Austronesian families, considering in both cases, fifty different languages. The resulting trees are similar to those of previous studies, but with some important differences in the position of few languages and subgroups. We believe that these differences carry new information on the structure of the tree and on the phylogenetic relationships within families.

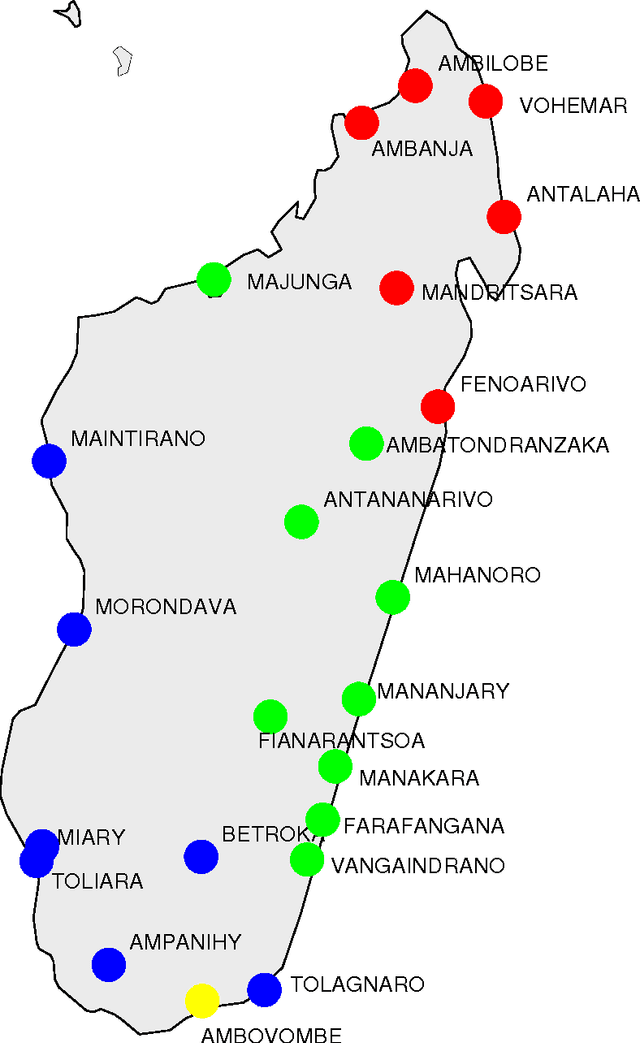

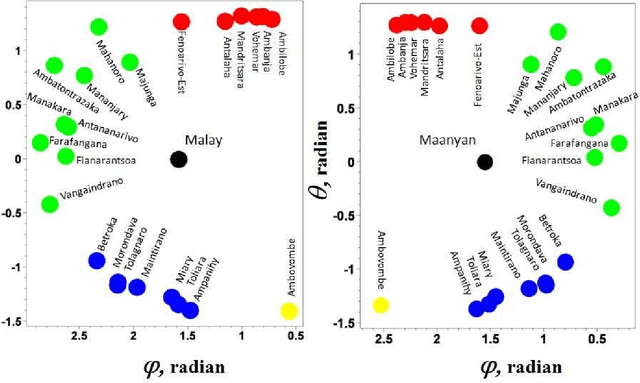

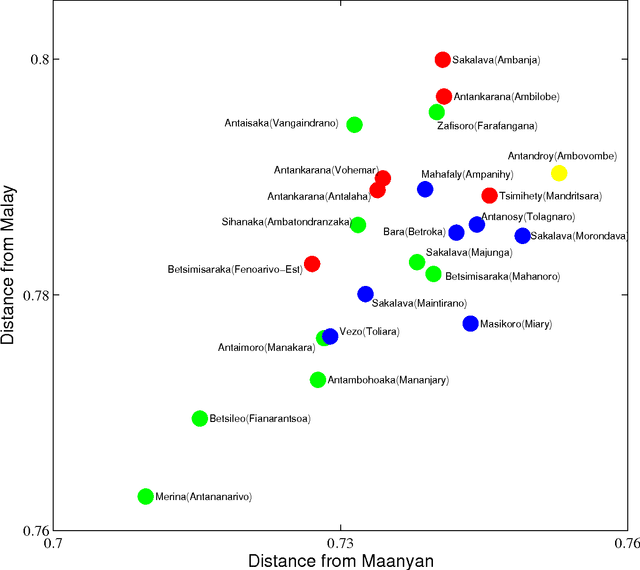

The settlement of Madagascar: what dialects and languages can tell

Jul 21, 2011

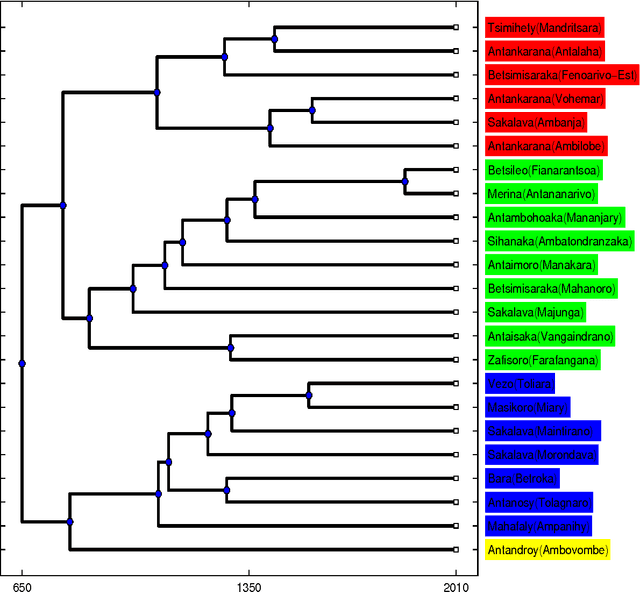

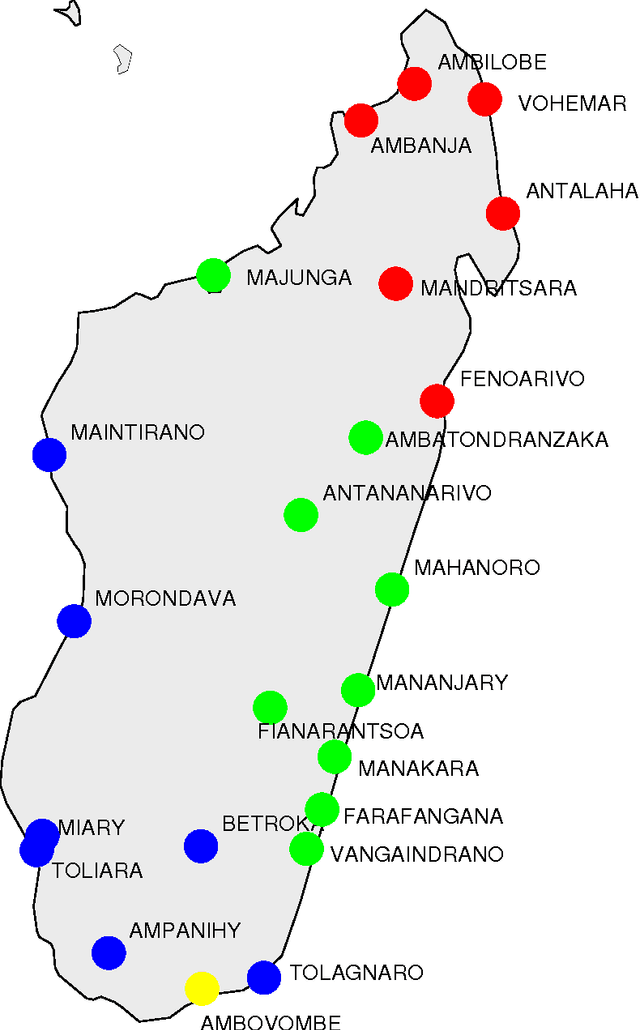

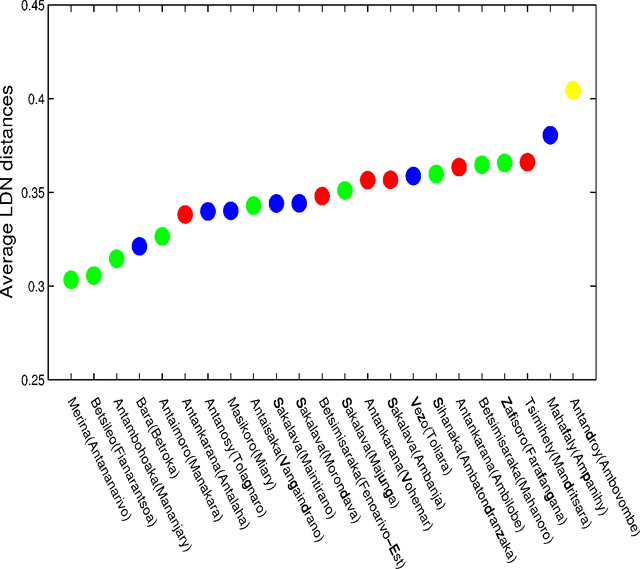

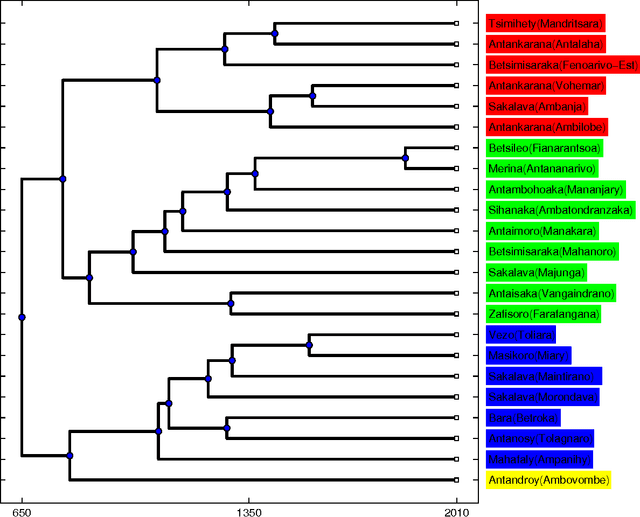

Abstract:The dialects of Madagascar belong to the Greater Barito East group of the Austronesian family and it is widely accepted that the Island was colonized by Indonesian sailors after a maritime trek which probably took place around 650 CE. The language most closely related to Malagasy dialects is Maanyan but also Malay is strongly related especially for what concerns navigation terms. Since the Maanyan Dayaks live along the Barito river in Kalimantan (Borneo) and they do not possess the necessary skill for long maritime navigation, probably they were brought as subordinates by Malay sailors. In a recent paper we compared 23 different Malagasy dialects in order to determine the time and the landing area of the first colonization. In this research we use new data and new methods to confirm that the landing took place on the south-east coast of the Island. Furthermore, we are able to state here that it is unlikely that there were multiple settlements and, therefore, colonization consisted in a single founding event. To reach our goal we find out the internal kinship relations among all the 23 Malagasy dialects and we also find out the different kinship degrees of the 23 dialects versus Malay and Maanyan. The method used is an automated version of the lexicostatistic approach. The data concerning Madagascar were collected by the author at the beginning of 2010 and consist of Swadesh lists of 200 items for 23 dialects covering all areas of the Island. The lists for Maanyan and Malay were obtained from published datasets integrated by author's interviews.

Phylogeny and geometry of languages from normalized Levenshtein distance

Apr 29, 2011

Abstract:The idea that the distance among pairs of languages can be evaluated from lexical differences seems to have its roots in the work of the French explorer Dumont D'Urville. He collected comparative words lists of various languages during his voyages aboard the Astrolabe from 1826 to 1829 and, in his work about the geographical division of the Pacific, he proposed a method to measure the degree of relation between languages. The method used by the modern lexicostatistics, developed by Morris Swadesh in the 1950s, measures distances from the percentage of shared cognates, which are words with a common historical origin. The weak point of this method is that subjective judgment plays a relevant role. Recently, we have proposed a new automated method which is motivated by the analogy with genetics. The new approach avoids any subjectivity and results can be easily replicated by other scholars. The distance between two languages is defined by considering a renormalized Levenshtein distance between pair of words with the same meaning and averaging on the words contained in a list. The renormalization, which takes into account the length of the words, plays a crucial role, and no sensible results can be found without it. In this paper we give a short review of our automated method and we illustrate it by considering the cluster of Malagasy dialects. We show that it sheds new light on their kinship relation and also that it furnishes a lot of new information concerning the modalities of the settlement of Madagascar.

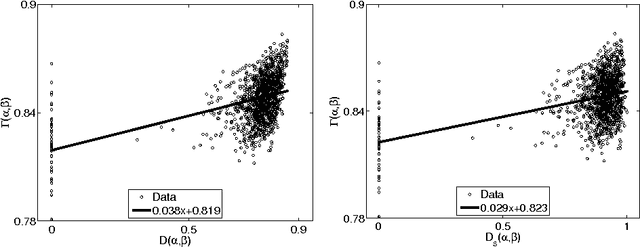

Measures of lexical distance between languages

Dec 09, 2009

Abstract:The idea of measuring distance between languages seems to have its roots in the work of the French explorer Dumont D'Urville \cite{Urv}. He collected comparative words lists of various languages during his voyages aboard the Astrolabe from 1826 to 1829 and, in his work about the geographical division of the Pacific, he proposed a method to measure the degree of relation among languages. The method used by modern glottochronology, developed by Morris Swadesh in the 1950s, measures distances from the percentage of shared cognates, which are words with a common historical origin. Recently, we proposed a new automated method which uses normalized Levenshtein distance among words with the same meaning and averages on the words contained in a list. Recently another group of scholars \cite{Bak, Hol} proposed a refined of our definition including a second normalization. In this paper we compare the information content of our definition with the refined version in order to decide which of the two can be applied with greater success to resolve relationships among languages.

Lexical evolution rates by automated stability measure

Dec 09, 2009

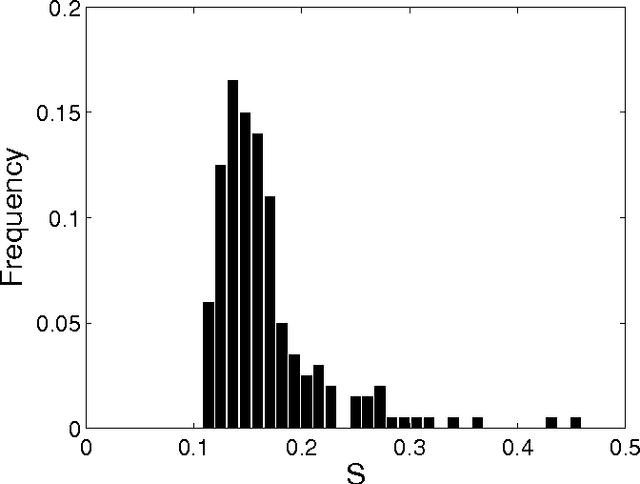

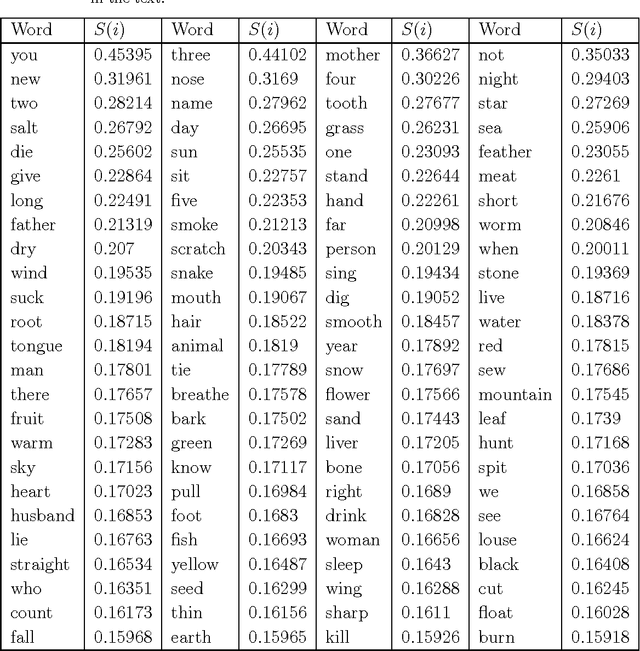

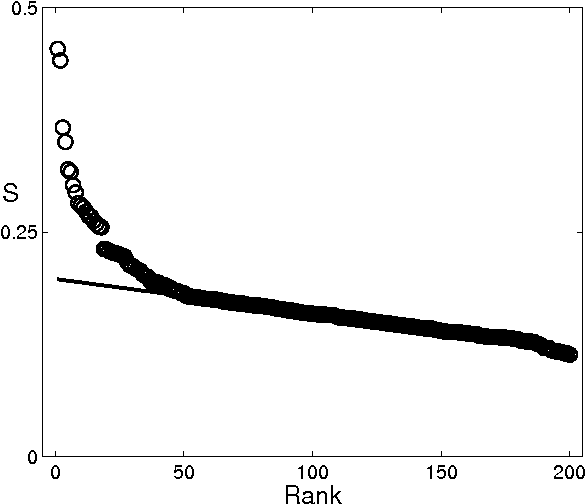

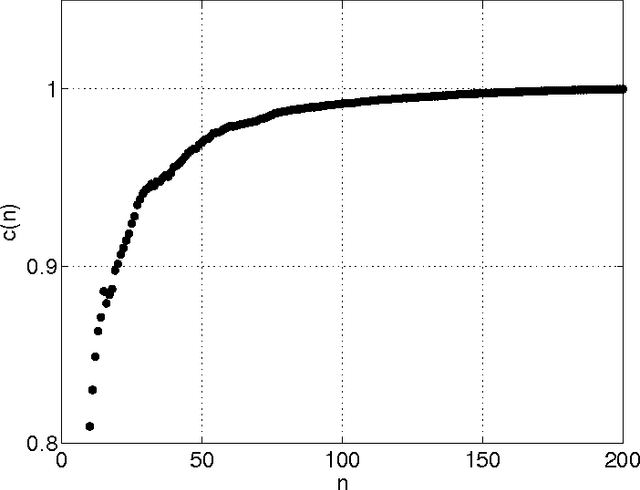

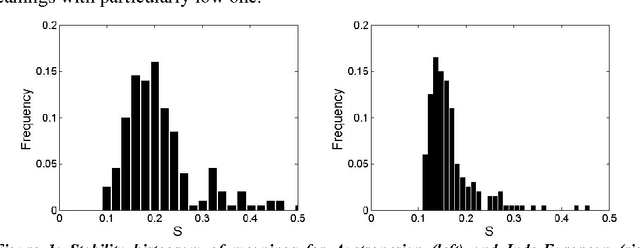

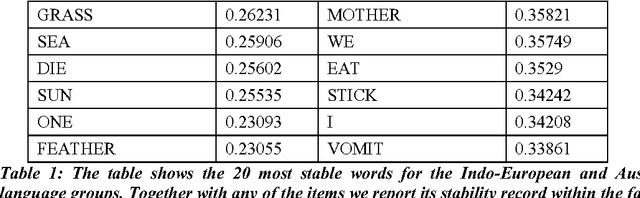

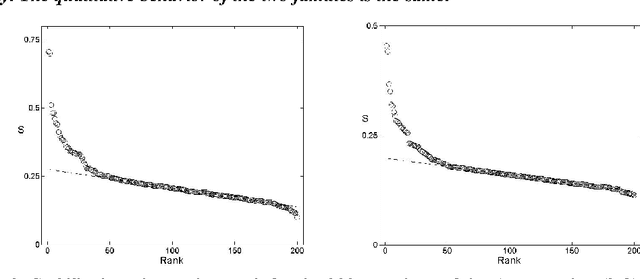

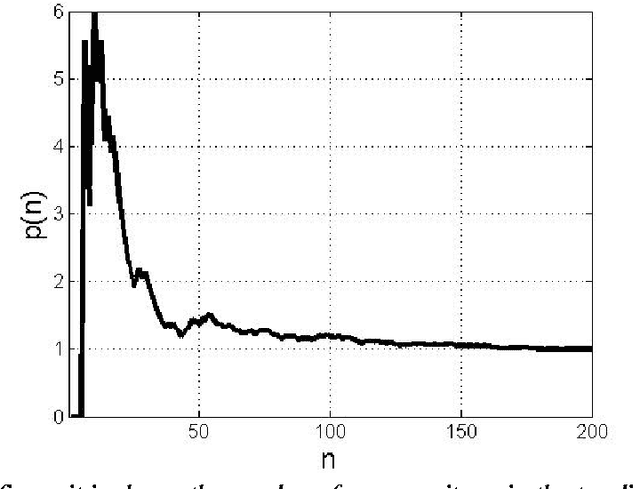

Abstract:Phylogenetic trees can be reconstructed from the matrix which contains the distances between all pairs of languages in a family. Recently, we proposed a new method which uses normalized Levenshtein distances among words with same meaning and averages on all the items of a given list. Decisions about the number of items in the input lists for language comparison have been debated since the beginning of glottochronology. The point is that words associated to some of the meanings have a rapid lexical evolution. Therefore, a large vocabulary comparison is only apparently more accurate then a smaller one since many of the words do not carry any useful information. In principle, one should find the optimal length of the input lists studying the stability of the different items. In this paper we tackle the problem with an automated methodology only based on our normalized Levenshtein distance. With this approach, the program of an automated reconstruction of languages relationships is completed.

Automated words stability and languages phylogeny

Dec 05, 2009

Abstract:The idea of measuring distance between languages seems to have its roots in the work of the French explorer Dumont D'Urville (D'Urville 1832). He collected comparative words lists of various languages during his voyages aboard the Astrolabe from 1826 to1829 and, in his work about the geographical division of the Pacific, he proposed a method to measure the degree of relation among languages. The method used by modern glottochronology, developed by Morris Swadesh in the 1950s (Swadesh 1952), measures distances from the percentage of shared cognates, which are words with a common historical origin. Recently, we proposed a new automated method which uses normalized Levenshtein distance among words with the same meaning and averages on the words contained in a list. Another classical problem in glottochronology is the study of the stability of words corresponding to different meanings. Words, in fact, evolve because of lexical changes, borrowings and replacement at a rate which is not the same for all of them. The speed of lexical evolution is different for different meanings and it is probably related to the frequency of use of the associated words (Pagel et al. 2007). This problem is tackled here by an automated methodology only based on normalized Levenshtein distance.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge