Fintan Costello

Systematic Bias in Sample Inference and its Effect on Machine Learning

Jul 03, 2023Abstract:A commonly observed pattern in machine learning models is an underprediction of the target feature, with the model's predicted target rate for members of a given category typically being lower than the actual target rate for members of that category in the training set. This underprediction is usually larger for members of minority groups; while income level is underpredicted for both men and women in the 'adult' dataset, for example, the degree of underprediction is significantly higher for women (a minority in that dataset). We propose that this pattern of underprediction for minorities arises as a predictable consequence of statistical inference on small samples. When presented with a new individual for classification, an ML model performs inference not on the entire training set, but on a subset that is in some way similar to the new individual, with sizes of these subsets typically following a power law distribution so that most are small (and with these subsets being necessarily smaller for the minority group). We show that such inference on small samples is subject to systematic and directional statistical bias, and that this bias produces the observed patterns of underprediction seen in ML models. Analysing a standard sklearn decision tree model's predictions on a set of over 70 subsets of the 'adult' and COMPAS datasets, we found that a bias prediction measure based on small-sample inference had a significant positive correlations (0.56 and 0.85) with the observed underprediction rate for these subsets.

Surprisingly Rational: Probability theory plus noise explains biases in judgment

Apr 30, 2014

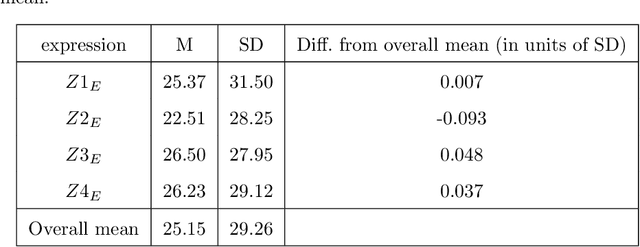

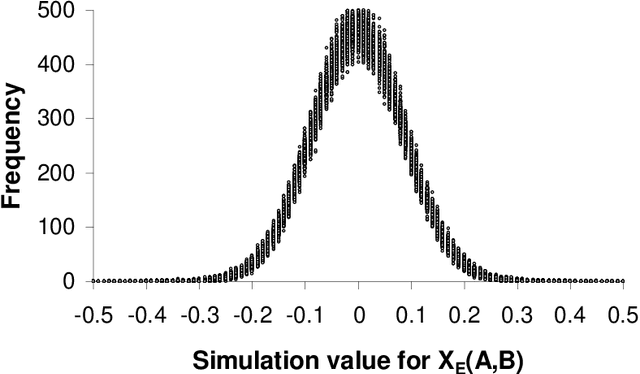

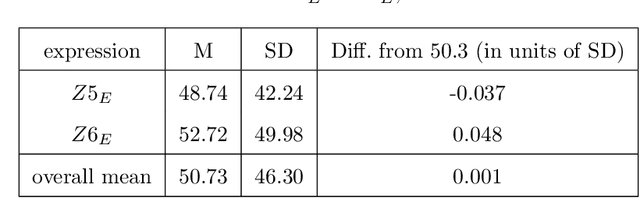

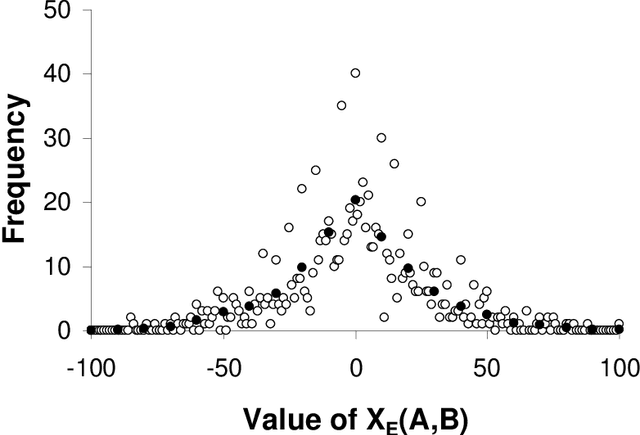

Abstract:The systematic biases seen in people's probability judgments are typically taken as evidence that people do not reason about probability using the rules of probability theory, but instead use heuristics which sometimes yield reasonable judgments and sometimes systematic biases. This view has had a major impact in economics, law, medicine, and other fields; indeed, the idea that people cannot reason with probabilities has become a widespread truism. We present a simple alternative to this view, where people reason about probability according to probability theory but are subject to random variation or noise in the reasoning process. In this account the effect of noise is cancelled for some probabilistic expressions: analysing data from two experiments we find that, for these expressions, people's probability judgments are strikingly close to those required by probability theory. For other expressions this account produces systematic deviations in probability estimates. These deviations explain four reliable biases in human probabilistic reasoning (conservatism, subadditivity, conjunction and disjunction fallacies). These results suggest that people's probability judgments embody the rules of probability theory, and that biases in those judgments are due to the effects of random noise.

Add to Chrome

Add to Chrome Add to Firefox

Add to Firefox Add to Edge

Add to Edge